THE F-86C/YF-93 "SABRE"

by Larry Davis

What Is It? Sabrejet Classics issue

9-3. Well, we sure didn't fool anyone with our subject last issue. Several

members identified the photo as a North Amencau Aviation YF-93A/F-86C. Thanks

to all that sent notes and information about the subject airplane. With that

in mind, we thought we should do the story of the F86C Sabre.

So what exactly was the it? In 1946, the Air Force had recognized that all

the current jet fighter designs were lacking in one critical area - range.

The P-86A with 200 gallon ferry tanks under the wings, had a ferry range of

1052 miles. The two other major jet fighter types, the P-80 and P-84, were

similar. And inflight refueling was still a glimmer in the eyes of the engineers.

And Strategic Air Command wanted jet fighters to escort their long range bombers

to targets, which were now envisioned to be deep in the Soviet Union - and

far outside the range of any jet fighter. They were known as "penetration

fighters".

In late 1947, with the Penetration Fighter requirement in mind, North American engineers started a project to both increase the range and the speed of their swept wing fighter. Any increase in range required an increase in fuel capacity, either in bigger internal tanks or through droppable underwing fuel tanks. The engineers enlarged the entire fuselage in length, width, and depth. In addition, the wing span was increased 1' 8" on each wingtip.

Both of these changes increased the internal fuel capacity from 435 gals. in the F-86A to an incredible 1561 gals internally! And since the new penetration fighter used a modified F-86A wing, it was able to carry any of the underwing tank designs available, including the 200 gal. ferry tanks. That brought total gallonage to 1961. Unrefueled range was estimated to be in excess of 2000 miles.

All of this extra fuel meant the airplane gross weight was increased a corresponding amount, from 15,876 lbs combat weight in the F-86A, to 26,516 lbs in the F86C. The J47 didn't have enough power to keep the much heavier fighter in the transonic speed range necessary for jet combat. Pratt & Whitney had an engine available, the J48-P-6 engine which had an afterburner. The e J48 was rated at 6,250 lbs static thrust, with 8750 lbs thrust available in afterburner.

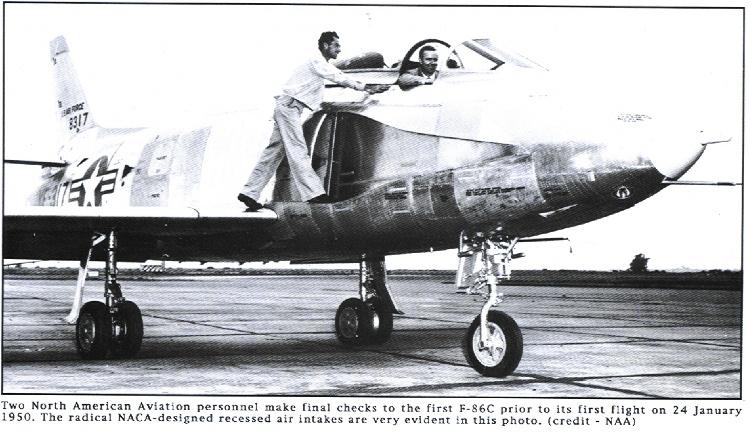

The North American engineers decided to incorporate other new items which were just then becoming available such as the SCR-720 search radar and 20mm cannons (six) in place of the standard .50 caliber armament. The heavier weight necessitated a dual-wheel main lauding gear. With the radar mounted in the nose where the air intake was on the F-86A, the engineers designed a novel set of flushmounted NACA-designed air intakes on each side of the forward fuselage. The center of the fuselage was slightly concave, giving the aircraft a distinctive "wasp-waist" appearance.

Other portions of the new penetration fighter retained their F-86A ancestry - the canopy/windscreen design, both vertical and horizontal tail design, cockpit and ejector seat, nose gear assembly, and the main portion of the wing. With all that being common with the F86A, it was natural that the aircraft be designated in the F-86 family. But Air Force decided that there were too many design changes in the penetration fighter design, and redesignated the airplane as the F-93. (The same thing occured with the initial F-86D design which was originally designated as the F-95.)

In December 1947, Air Forced ordered two prototypes of the new fighter. Six months later, Air Force added a further 118 aircraft to the contract - 18 months prior to the first airplane coming off the assembly line! However, in February 1949, Air Force suddenly cancelled the entire project. The reason was two-fold. First was the development of the B-47 Stratojet bomber, which was estimated to be so fast that it wouldn't need any fighter escort. Second was a drastic reduction in the overall defense budget.

But North American already had the two prototypes under production and made the decision to go ahead and complete the two (now-designated) YF-93As. The first aircraft, serial 48-317, made its first flight on 24 January 1950. The second YF-93A #48-318, followed shortly thereafter. In the late summer of 1950. Air Force held a fly off between the three "penetration fighter" designs - the McDonnell XF-88 Voodoo, Lockheed XF90, and the YF-93A. The Evaluation Board declared the XF-88 as the winner of the fly-off. However, the rapid development of the XB-47 and the even more formidable XB-52, made the decision null and void. There was simply no need for a penetration fighter aircraft.

Air Force took control of the two YF-93As and gained the following results from flight tests. The YF-93A's top speed was 708 mph at sea level, and 622 mph at 35,000 feet. The range was almost exactly what the engineers bad predicted, 1967 miles. Rate of climb with the J48 in 'burner was 11,9 60 feet/minute. Pretty impressive for an airplane that would never see production. When Air Force was through with the YF-93As, they turned both prototypes over to the NACA's Ames Laboratory at Moffett Fi ld for further tests and evauation.

NACA soon fitted the second YF-93A

with standard intakes over the original flush-mounted units. It was found

that the conventional air intakes increased performance and the first YF-93A

was subsequently equipped with a set for further tests. Both aircraft finished

their service careers flying as chase aircraft to the newly developed Century

Series of fighters that would replace the entire F-86 series. Both air craft

were removed from service in the late 1950s and scrapped.

Radar Lock-on

The Sabre's Radar is Locked on...

S/L ANDY MacKENZIE, RCAF (Ret)

Sabrejet Classics is proud to lock the Sabre's radar on Squadron Leader Andy MacKenzie, RCAF (Ret). His story is truly a remarkable one, spanning World War II and the Korean War.

Andy achieved "ace" status in World War 11, downing 8.5 Luftwaffe aircraft. Three of them went down in one day, 20 December 1943 - in only ninety seconds!! But his tour was not without a couple of rough spots. He was shot down twice by AAA. And one of those times it was by U.S. gunners over Normandy's Utah Beach. The other time, his Spitfire was hit by enemy flak over Caen while he was flying at 18,000 feet, and he was forced to dead-stick the Spit in friendly territory.

As exciting and spectacular as

his WW2 exploits were, Andy would probably not be appearing in Sabrejet Classics

were it not for his brief (?) exchange tour flying the

F-86 with the 51st Fighter Group in Korea. On 5 December 1952, his fifth mission,

Andy was shot down again. And again it was American gunfire that brought him

down! It was one of those terrible times when, in the heat of battle, his

Sabre was mistaken for a MiG-I 5 by another Sabre pilot.

Andy successfully ejected, but was captured by the Chinese Reds, and remained a prisoner until 5 December 1954 - long after the 27 July 1953 cease fire went into effect ending the Korean War. Eighteen months of those two years were spent in solitary confinement. While in captivity, Andy was reminded by his captors that no one even knew he was alive, and he could easily be killed. But Andy steadfastly refused to sign any of the statements accusing the United States of war crimes. Only when other released prisoners asked, "Where the hell is Andy MacKenzie?", was Andy finally returned to freedom.

Andy and his wife Alison, live in Oxford Station, Ontario, and they attended the most recent reunion of the F-86 Sabre Pilots Association. Now 81 years young, Andy proudly recalls his twentyseven years as an RCAF fighter pilot. In all, Andy earned twelve medals, including the Distinguished Flying Cross awarded for the downing of the three German aircraft in one day. He retired in 1966, and retains his sense of humor. When asked recently what went through his mind when he squeezed the triggers on his ejection seat over Korea, Andy said, "I wonder if this damn thing works!"

The Association points with pride

to our esteem member and friend, S/L Andy MacKenzie. And we look forward to

enjoying his company at future reunions.

THE AIR FORCE MUSEUM SALUTES

"THE FORGOTTEN WAR - KOREA

As you walk into the halls of the US Air Force Museum at Wright Patterson

AFB near Dayton, Ohio, the first thing you will see will be very familiar

to pilots who served with the 4th Fighter Wing at Kimpo - the torii that led

from the 336th Squadnon Operations hut to the flightline. It said "MiG

Alley - 200 Miles". With that as a beginning, a recently opened display

of memorabilia and photos will take the visitor back to the years between

1950 and 1953, when airmen of the 5th Air Force and far East Air Forces fought

the first of many struggles against communism - the Korean War, an all but

forgotten saga in the great military history of America.

A hallowed silence greets visitors as they enter the new exhibit. Soon, the quiet yields to a faint mental whir of wartime activity at places with names like Kimpo, Suwon, Taegu, Pusan, Itazuke, Yokota, Kadena, and too many others to list completely. Your eyes scan the images before you - uniformed maniquins, personal artifacts, films and sound bites, all set against a majestic mountainous backdrop, transport the viewer rapidly through a time portal back to those dark cold days.

The Air Force Museum's exhibit commemorates the 50th Anniversary of the Korean War. It was officially opened to the public in October 2000, and is slated to remain intact through the anniversary of the end of that almost forgotten conflict in July 2003. Entitled "Korea Remembered: The US Air Force Comes Of Age", the exhibit recalls The Forgotten War by spotlighting the emergence of the modem Air Force and its evolution into a lethal air arm, although the service itself was in its infancy.

The theme of the exhibit is to show the Air Force in transition from the Army Air Force in World War 2, to a modem Air Force ready to tackle the challenges of the new Cold War. Jeff Duford, USAFM Research Division: "We wanted to put the Korean War in a greater historical perspective than just to recall wartime events. After all, this was the first test for the new independent Air Force since its inception in 1947."

The exhibit uses striking visual effects like large color images of aircraft and crews, life-like habitats depicting what it was like for the troops in Korea. The exhibit tries to integrate the combat in Korea with the other elements to illuminate the role air power played in helping defend South Korea from its communist aggression in the north. And to honor the service of all those who wore the uniform in those difficult times. The exhibit is aimed for those Air Force veterans who served in Korea. It is their moment to stand back and be recognized. And especially a time to remember all those who did not come back. "We wanted to create something tha would grab the visitors attention and draw them in to read about those veterans and their mission of so long ago", Duford said.

About 75% of the 190 exhibit photos are in color, helping to lift the war from black and white pages of history and bring it to life. The exhibit features eight correctly uniformed mannequins, three videos, and more than 100 artifacts. It is divided into eight theme areas, matching the Air Force missions in Korea.

These include air superiority, strategic bombing, inerdiction, close air support, reconnaissance, airlift, air rescue and evacuation. The text is punctuated by relevant quotes from historically significant Korean War-era figures.

Through these theme areas, the exhibit seeks to impart a more intimate understanding of the Korean War as a watershed event for air power and its evolving doctrine, The exhibit designers did this by emphasizing how sustained air superiority, combined with a campaign of strategic bombing and interdiction, made the war very costly for the communists and helped force a ceasefire that endures to this day.

"Even though it was vital, fighter combat was numerically just a small portion of the total Air Force Mission", said Durford. "We also wanted to focus attention on other combat roles as well as critical support functions in which so many personnel served."

The first thought of most people regarding the Korean War is that of silver F-86s and MiG jet fighters mixing it up over the Yalu River. But the Museum exhibit seeks to reach beyond the aircraft and air campaigns that were waged, and show the many sides and missions of all those who served.

"While the aircraft are important, not everyone relates to the airplanes", said Connie Johnson Chapman, one of the exhibit designers. "I try to bring out the human element to which a broad audience can relate. We wanted to tell the story of veterans and communicate a realistic sense of the environment in which they served."

"The photos try to portray a variety of situations. "You can tell by looking at people in the exhibit photos, that there was a real camarderie among them. Plus we wanted to show the wide range of roles that people filled. Not everyone was a pilot."

But if you want to see the airplanes,

they are there. You can take your grandkids and show them the type of airplane

you flew or worked on. Almost every type is on display, from an F-86A to the

T-6G Texan, B-29 to H-19A, F-82G Twin Mustang to C-54D flying ambulances.

Some are displayed in the Korean 'bay' of the museum, some are displayed in

other areas of the vast museum. For those who have never been there, make

sure you have at least one full day available to view everything. The US Air

Force Museum is open from 9am to 5pm, 7 days a week, and almost every day

of the year. Make plans for a trip, it's worth the effort. And for those in

the Sabre Pilots Association, the outdoor park has a memorial dedicated to

and from our association.

"E" FLIGHT FROM CHITOSE

by Cliff Winter

October 1952, the 'hot war' in Korea was winding down and the 'Cold War' was

warming up. The occupation of Japan had ended in April, leaving the Far East

Air Force responsible for air defense of that island nation. I was assigned

to the 41st Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Johnson AB, having just completed

a tour in F-80s; with the 36th FBS at Suwon. In a few months the 41st would

convert to F-86s.

My family had arrived in Japan about three months before, and we were looking forward to a couple of years without separation, when suddenly I received orders placing me TDY with Flight E (Provisional). I had no idea that the great flying would almost compensate for the new separation.

Flight 'E' was hatched because of Japanese concern over the intrusion of Russian MiGs over Hokkaido. MiG flights were coming down from bases in the northern Kuriles and on Sakhalin. FEAF air defenses consisted of a single squadron of F-84s at Chitose, and an early warning radar at the northern tip of the island. Major James Stewart, CO of the 41st, was given the job of creating the unit and selecting personnel, including pilots with F-86 experience. Luckily, I had 150 hours in the F-86 right out of flight training.

We were based at Chitose. Lacking

experience in formIng such an organization,

Maj. Stewart dug out a TO&E;, and drew the organizational chart in the

dirt of the hanger floor. He called us together and had us stand in our assigned

slot so he could tell which jobs were still open and assigned them on the

spot.

I was eager to get a chance at the MiGs in a competitive Fighter like the '86 after some frustrating encounters flying F-80s in Korea. My flight then, had a few guys who, like me, had an itch to tangle with the MiGs. The prospect of air to air combat seemed like a ball 'in comparison to the impersonal ground fire we faced on our interdiction minions.

We conserved our fuel after 'working on, the railroad', so we could stay in the area a little longer. We'd discovered that after the '86s had left for home, a few MiGs would come looking for the defenseless F-80s. On a few missions, we managed to find each other. All we had to do was see them and turn into them and they were unable to get into position for a decent shot. Of course, we seldom got a shot at them either. But the game was a ball!! Natunilly, if they kept attacking, we had to keep turning and couldn't head for home, using up what was left of our fuel. They never figured this out and a couple of times we landed on fumes.

I cine very close to scoring on

one mission. After doing our usual shoot 'em up along the MSR, we were jumped

by what appeared to be a single MiG. I called

"Break right!", but my wingman called "Red Lead, roll out,

you've got one passing under you." Sure enough, less than 200 feet ahead

and low, a MiG had tried to slow down to match our turn. He misjudged and

now realized he'd just made an "Oh s--t!" blunder. He was so close

that he filled 1/3 of my windscreen.

In an instant I had the pipper centered on his tailpipe. He was dead meat! I squeezed the trigger and waited to hear the chatter of the six .50s. What I got was "Pop! Pop!". I was out of ammo! And the MiG pilot was out of there too soon for my wingman to slide over for a shot. So much for the highlight of my Korea tour.

After getting Flight E organized,

our first task was to pick up twelve new F-86Fs at Kizarazu. The F model was

new to me on top of the fact that I'd flown nothing but

F-80s; in over a year. So I did a lot of smiling during the refresher check-out.

In early December, the pilots and aircraft flew to Chitose.

Upon arrival, the first thing I noticed was the snow. The second was the temperature. I had come face to face with the fact that we had moved a lot closer to the Arctic Circle. Snow fell often, and almost always in the form of short intense showers lasting 10-20 minutes. The shortage of alternates, combined with the snow showers, made for many a 'pucker moment'- By the end of December, the taxiways and runway were like tunnels. Mammoth snow blowers capable of getting the snow to the tops of 35 foot high piles, kept Chitose open most of the time.

An F-84 pilot found the deep snow to be a blessing when he landed short and wiped out the main landing gear. My wingman, Pat McGee, watched the '84 approach and landing. It became obvious that the '84 was going to land short. Pat said it was a spectacular sight when that '84 disappeared into the snow about 1000' short of the over run, remaining hidden until it bunt into sight with snow flying in all directions, and sliding more than 2000' straight down the runway. That left us with two choices, one was poor and the other lousy. We could land over the '84 and try to stop on the remaining 3000' of ice runway. Or we could try and make one of the alternates on what was left of our fuel. Being cocky fighter pilots, we chose the former. We'd have 2500' of runway, plus the over run to get stopped in. And if that wasn't enough, the big snow bank at the end "looked pretty soft"! As it turned out, I was actually able to turn off on the last taxiway. Pat also got stopped but blew a tire when he hit one of the few dry patches of runway.

Flight E's mission was to discourage the MiGs from entering Japanese airspace. This was easier said than done as them was no GCI capability on Hokkaido. The only radar in the area was an early warning station on the northern tip. They were able to tell us - by landline! - the location in latitude and longitude of the intruder, but no intercept information.

Once airborne we had no radio contact with the radar guys, and were left to find a couple of very tiny aircraft in a very large sky. To my knowledge, no contact was ever made as a result of any of these scrambles. Normally, we patrolled near the area where the MiGs might be. Apparently, this was successful because the MiGs stayed well cear of us. And reports of overflights dropped considerably. Occasionally, our guys reported seeing a flight of MiGs in the distance, making tracks for home.

To give us more patrol time, a deployment base was set up at Kenebetsu, about 200 miles north of Chitose. Kenebetsu was an old Japanese fighter base, but was now deserted. Six of our airmen, including a cook, starter unit, fuel truck, and practically nothing else, went to Kenebetsu to provide refueling and alert capability. The men slept in tents and cooked over open fires. We had to eat with our gloves on. To us pilots, it was a pretty lousy existence. But the ground crew seemed to enjoy it.

Wben the weather permitted, a flight of F-86s would leave Chitose, fly a patrol over the east coast and land at Kenebetsu. After refueling and lunch, we would repeat the patrol and head back to Cohost. Bemuse we were flying into the teeth of the jet stream, which often exceeded 150 knots and snow showers were a likely possibility at Chitose, fuel reserve was always a serious concern. By late January 1953, I still had sighted no more than a couple of MiG flights. I was scheduled to patrol what we knew as the MacArthur Line, a line established between Sakhalin and Hokkaido. Julian Logan was my wingman. Pat McGee and Abe Lincicome had the other element. We all liked having Pat with us because of his unbelievable eyesight. He could spot another aircraft long before anyone else. I felt that a decoy operation might bring the MiGs across the MacArthur Line where they'd be fair game.

I asked Pat to follow us by 15 minutes, and to fly where his flight would leave an obvious contrail. I planned to penetrate the southern coast of Sakhalin above the cons. This would allow the Russians to scramble the MiGs before we started our turn back. My hope was that the MiGs would head south, and instead of finding us, they'd see Pat's flight clearly visible heading north. And that's what happened.

It was late afternoon when we spotted Pat's flight clearly visible heading north. With absolutely lucky timing, a flight of MiGs was headed south, conning brightly. I called them out to Pat, who acknowledged and said he was steady at 27,000'. It was the kind of perfect setup that all fighter pilots dream about altitude advantage and surprise!

We punched off our tanks, hoping the bad guys wouldn't notice them flashing in the sun. I was already picturing myself painting a big red star on the side of my Sabre. We were in perfect position at about 36,000'. Unfortunately, we were slightly east of their position and looking into the sun. As we started our dive, the two flights started to turn toward one another, putting them in a circle with Pat's flight turning through east and the MiGs turning through west.

During ourdive we were headed into the sun and I lost sight of both flights for a few seconds. I made a quick judgment as to which flight was which, and here's where I blew it. I closed on the No. 2 man with everything in my favor. I was looking right up his tailpipe from. about 2500' and closing rapidly. I was actually starting to squeeze the trigger when I suddenly realized it wasn't a MiG. It was an '86. I had come within a split second of shooting down Abe Lincicome. We still had plenty of excessive air speed so we pulled up and turned north expecting the MiGs to be headed in that direction. But they turned west and were making tracks out of there. Once again, I had missed my chance to finally get a MiG. We tried the decoy operation a few more times but the MiGs failed to fall for it again.

But chasing Migs wasn't our only source of entertainment. Before the F-86, few of us had had the opportunity to break the sound barrier. So occasionally, we would launch with a cean aircraft to see just how fast it would go. We'd climb to about 30,000, point the nose straight down with full power, and stomp on the floor to get the Mach meter to indicate mom than 1.0. The most we could get was about 1.04. We also learned two other things - start your pullout at above 10,000' to avoid colliding with the planet, and not to use Chitose as an aiming point. How were we to know the post commander's wife lived there, and she had precious dishes in her closet. We were firmly told to find a new playground.

At Chitose, I had been adopted by a lovable, wooly puppy peculiar to the harsh winters of Hokkaido. With my TDY over, I couldn't leave Dusty behind. But getting her back presented a problem. I was to fly an '86 back which my replacement would return in. Dusty was pretty calm so I decided to take her with me in the airplane. In spite of his obvious doubts, the crew chief passed her to me after strapping me in. Before taking the runway, I ran the engine to full power. Dusty seemed to accept this so off we went. The flight was uneventful and both the dog and I arrived none the worse for wear. I wish I had a picture of the crew chief's eyes at Johnson when I opened the carropy and handed Dusty to him.

Flight E (Provisional) was a truly

unique and enjoyable experience.

Memories of Great Fighter Pilots

"The Bloody Great Wheel"

HARRISON R. THYNG

Larry Davis

with

James R. Thyng

Harrison R. Thyng was a helluva

pilot, one of only seven to become fighter aces in both WWII and Korea. More

than that, this fighter pilot was a leader of men. Few officers have experienced

the assumption of command as young as did Harry Thyng and consistently commanded

most of the organizations to which he was assigned from First Lieutenant through

the rank of Brigadier General. Of those magnificent seven, only Harrison Thyng

became a general officer.

He was a native of New Hampshire where it is said, men are made from granite.

Born in 1918, he grew up in Barnstead and Pittsfield before leaving to join

the Amy Air Corps (USAAC) in 1939. Twenty seven years later he returned to

New Hampshire, a Brigadier General and veteran of many battles.

He had fought in Europe as Commander of the 309th Squadron, 3 lst Fighter Group flying British Spiffires. He was credited with the USAAFs first encounter with a FW 190, on 8 November, 1942, near Shoreham, England. Shipped to North Africa, Harry Thyng led his squadron into Oran and shot down a Vichy French Dewoitme 520 fighter on that first mission. One hundred sixty one missions later, battle weary and wounded, this fighter was sent home. A full Colonel at age 26, Harry became commander of the 413th Fighter Group flying P-47Ns. He led the group across the Pacific to le Shima in June, 1945 flying 22 missions before the atomic bomb ended it all. But, his fighting days were not yet complete.

Next it was Korea; and he answered the call. He was assigned as Commander of the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing, Kimpo, Korea on 1 November, 1951. He inherited a unit outmanned and out gunned by 750 MiG-15s positioned on five air bases north of the Yalu River. With not enough equipment and parts to effectively counter the overwhelming odds, he jumped the chain of command and risked his career to make something happen.

In a December, 1951 secret message he penned, "Personal to Vandenberg (Air Force Chief of Staff) from Thyng. I can no longer be responsible for air superiority in northwest Korea!" His F- 86 Sabres were so badly outnumbered, Thyng feared that in spite of a favorable kill ratio, he was losing the war. He had listened to his maintenance personnel and S/Sgt Fred Newman told him "Colonel, my crew chiefs are working 24 hours but we don't have the parts we need, we don't have the wing tanks, and if we had to put up a maximum effort tomorrow morning, we wouldn't be able to do it!"

S/Sgt Gordon Beem, and the Wing Adjutarit, Maj John Ross, didn't believe the commander understood the consequences of the message he was sending. Beem asked the Colonel if be really wanted to send the message. Col. Thyng replied, "Yes, there are too many lives at stake not to." The Colonel then climbed into his F-86 Sabre jet, -Pretty Mary and the Four Js", and flew to MiG Alley.

The problem began to be rectified within 96 hours. The new North American Tech Rep, Mr. Penney Bowen, arrived in Korea, bringing with him some $26,000.00 worth of badly needed parts. The AOCP rate started to drop dramatically at Kimpo, By early 1952 the in-commission rate had risen to over 75%, and air superiority over MiG Alley was never again in doubt. Of course, Col. Thyng's career took a big hit from all his superiors for a short time.

Walter Boyne wrote of the incident, 'From Longstreet at Gettysburg to von Paulus at Stalingrad to Walker in Korea, history is replete with stories of brave military leaders who would risk their lives in combat on a daily basis but would not risk their careers bucking their own superiors. In a stunning gesture defying the established order, Thyng did both."

Col. Harrison R. Thyng scored many more victories than the five that are credited to him by official sources. It is well known that he gave several of the victories to the wingmen that flew with him and kept him safe in the cold blue skies of MiG Alley. Wingmen never got any credit for their deeds. Thus after he had scored his 5th MiG, all further credits went to the pilots that watched his tail. Such was the leadership of Col. Harrison R. Thyng - "The Bloody Great Wheel" at Kimpo.

When Col. Thyng went home from Korea, he had good reason to feel good. On 29 September 1952, at Col. Thyng's going away dinner, General Glenn 0. Barcus, commander of 5th Air Force, named him one of the greatest fighters of all time. He had put together the most formidable air superiority force of any nation at that time. He was an ace in two wars, but also a leader willing to take risks for the benefit of his men. Col. Harrison R. Thyng, the premier fighter wing commander of his era, has now been all but forgotten.

In concert with the Pittsfield

Historical Society, his children - "The Four Js" am trying to ensure

that their father is remembered. They are seeking the funds to erect a monument

of granite for a New Hampshire patriot who must not be forgotten. Please consider

supporting this tribute to a true American hero who gave to his country all

that he had to give. For more information see Harry Thyng's website at:

www.pittsfield-nh.com/thyngmemorial.htm

Contributions are tax deductible; the Society is a 501 (c) (3) organization.

Please send any amount you feel is appropriate to:

Harrison R. Thyng Memorial

Pittsfield Historical Societ, Inc

13 Elm Street, P.O. Box 173

Pittsfield, New Hampshire 0326

"THE FALCONS"

THE 5TH AF AIR DEMONSTRATION

TEAM

via Paul Kauttu

In Sabrejer Classics' never ending

search for new and different things about the history of the F-86 Sabre, we

have uncovered a new jet demonstration team - the 5th Air Force "Falcons".

To be honest about it, we had never heard of them. But Paul Kauttu sent the

following information about the team.

The 5th AF "Falcons" may have been the youngest air demonstration

team ever formed. At one point, the average age was just 25, with a total

commissioned service time of barely 13 years total. The tem was formed in

mid-1956 by Lt.Col. Philip Lovelace, then CO of the 5th AF Standardization

& Indoctrination School at Naha, Okinawa. Lovelace made the first team

selections, then rotated back to the States.

That summer, after all the wing and squadron COs had completed the FAFSIS course, the school was closed down and the team was absorbed by the 18th Fighter Wing. 5th AF designated the team as their official' air demonstration team. They called themselves the "Falcons". The original team consisted of Capt. Paul Kauttu - Lead, Capt. John Hart on Left Wing, Capt. Albert Funk on Right Wing, and Capt. Alexander Hutnyak in the Slot. Later that year the team added Lt. Edgar Griskowski, Right Wing; Lt. George Bracke, Slot; and Capts. Paul Ash and Williant Spillers were named Spares.

The Falcons flew standard combat F-86Fs assigned to the 18th Fighter Wing. No special modifications for the air demonstartion mission were done to the airplanes. Each squadron ear-marked four airplanes for use by the team, with the team flying with each squadron on a rotational basis.

The routines consisted of a lot of Thunderbirds aerobatics - with some added spice. Maj. Bruce Carr, exLeader of the Aerojets team, and Lt.Col. Dick Catledge, ex-Leader of the Thunderbirds, helped design the Falcons' air show routines, with tips on speeds and formations.

Some of the added 'spice' included a maneuver when Capt. Hutnyak who flew Slot, would remain in the diamond formation during the landing approach. On a signal from Falcon Lead, Hutnyak would pull up into a loop, stall off his air speed on the top, drop his gear on the way down, and pull out into the landing. The other three Falcons flew a tight 360 overhead in a V, then landed. The maneuver was later discontinued at Hutnyales wife's requests!

The Falcons tem began their flight

demonstrations in the early summer of 1956, and were disbanded one year later

in 1957 when the 18th Wing converted to F-100 Super Sabres. Capt. Paul Kauttu

was promoted to Major and served with the Thunderbirds Air Demonstration Team

from September 1962 through February 1966, becoming Thunderbird Lead in 1965.

Book Review:

Just Lucky Enough

and

Black Marble

by: Ross Fisher

Mr. Ross Fisher has written and published two novels which follow an RCAF fighter pilot and a few of his friends through the skies over England and the North Atlantic during World War 2 (just Lucky Enough I, and over Korea (Black Marble ) where the hero serves as an exchange pilot with the 5 lst Fighter Wing.

The author has done extensive research for both of these fascinating novels, and his attention to detail adds a measure of authenticty that is not always found in works by historian-authors. In "Just Lucky Enough" ' we are treated to an inside view of what it was like to fly Hawker Hurncane fighters from merchant ships in the North Atlantic. Fighter pilots of today (and perhaps most fighter pilots from WW2) will shudder to learn that these intrepid pilots were catapult launched from the bow of a ship to intercept Luftwaffe bombers. Upon their return, the Hurricane pilot had to ditch next to his 'mother ship', and hopefully be retrieved from the icy North Atlantic. Our heros return to fight another day, and we accompany them to more normal operations flying Spitfires from land bases. Ross Fisher will make you feel like you were part of the action. In Korea, "Black Marble" takes the principle character from the earlier novel on a variety of adventures mainly involving air to air combat over MiG Alley. Again, Ron Fisher "tells it like it was", and readers who flew in Korea will recognize radio chatter and technical details woven into a thoroughly realistic story of adventure and daily life as seen through the eyes of our RCAF Sabre pilot. There is a surprise bonus to this story, dealing with Korean orphans, which reveals a very human side of our hero (and the author).

Do not expect to find either of these novels in your favorite book store. They're only available through Mr. Fisher at his home address. He can provide you with one or both of the limited edition novels. You'll want to enjoy them both and pan them on to your grandchildren as part of the answer to the eternal question, "What was it like Granddad?"

Ross Fisher

1291 Foxcraft Drive

Aurora, IL 60506-1243

(Each novel - $7.95 + $3.00 s&h;)

Review by Lon Walter