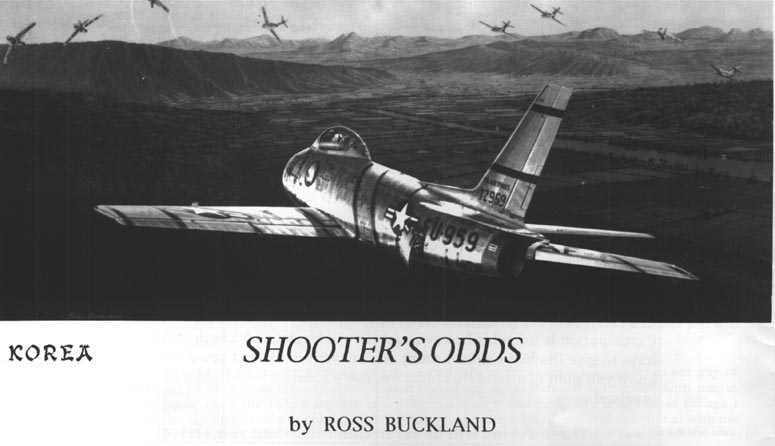

This story has heen copied from the 'Certificate Of Authenticity' for the lithograph "SHOOTER'S ODDS". The story and photo are published with the permission of Aeredrome Press, 3121 So. 7th St, Tacoma, WA 98405. The lithograph portray's Capt Ralph Parr's first encounter with the MiG-15 - sixteen of them!

Cruising at 43,000 feet, twenty miles south and parallel to the Yalu River, John Shark Flight of the 335th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing, had already armed their guns and checked their sights. In the lead was 1st Lt. Mervin Ricker, with Col. Robert Dixon as No.2, followed by the second element with 2nd Lt. Al Cox as No.3, and No.4 Capt. Ralph Parr on one of his early missions in F-86s. The weather was CAVU (ceiling and visibility unlimited) - perfect for hunting MiGs this 7th day of June 1953.

With the first call of 'bandit tracks' from ROMEO, the GCI controller at the forward radar station, Ricker called "Drop tanks!" On the flight's second swing to the northeast, Parr spotted a flight of MiGs coming from the upper left at an incredible closure rate. "John Shark, break left! MiGs close and firing!"

Fortunately, the MiGs, coming in from 90degrees off, went through 'hit and run' without causing any damage. Ricker had turned after them, but they flashed away and disappeared. With the two flights sepearated, Ricker told John Shark 3 to start a withdrawal. Cox decided to complete a final orbit and nurse his element back up to 41,000 feet, having lost several thousand feet in the break.

Glancing to his right, down at the Yalu, Parr noticed some movement and called it out as very low. Cox radioed back, "I can't see it! You take it, I've got you covered." During the briefing that morning, Al had told Ralph, who had extensive experience in fighters in a previous Korean combat tour in F-80s, that if Ralph called bogies Al couldn't spot, he would clear him and Al would follow.

Rolling over slowly, Parr began a split-S with full power, and headed straight down to intercept what he thought would be a couple of MiGs going south. Cox, seeing Parr roll over toward him, entered a right bank to pick up the Sabre visually as it crossed under him. But it never came by since it was going straight down. Shark 3 asked which way 4 had gone. Ralph replied, "Straight down. Come on down and find me"

With his G-suit fully inflated as the Sabre leveled off at 500 feet under maximum G, Parr tried to gulp some air as his near Mach One jet closed on the MiGs. "I had found my MiG. ..two...nope four...Whoops eight! NO SIXTEEN!" Ralph Parr, who had lived for nothing more than to fly fighters, now found himself alone in the middle of an angry hornet's nest, a whole squadron of 16 enemy aircraft - and he had them cornered!

Rapidly gaining on two flights of four MiGs, Ralph pulled the throttle back to slow his closure rate. Without hesitation, Parr thought to himself, "This may be my last chance with the war winding down. So as long as I'm going to do it, I may as well take the leader and turn the peasants loose!" Ralph lined up on the apparent leader of the eight MiGs as he closed inside of 3,000 feet. Out of the corner of his eye he noticed another eight MiGs to his left, then all hell broke loose as the eight in front broke in all directions.

Still closing, Parr jerked the throttle to idle, popped his speed brakes, and tracked the MIG leader as he pulled the trigger. The sharp curve of the tracers, and the slowing rate of fire got his attention - he was pulling Gs for all he was worth. Before he could let off, the gunsight fuse blew at over 9 Gs, and now he had no working sight.

Slowly overshooting, Parr watched the MiG leader reverse until they were canopy to canopy in a rolling scissors, each looking straight into the other's cockpit. Watching for an opportunity, Ralph saw the MIG pilot make a slight change. With a little forward stick and some rudder, Parr slid his Sabre behind the MiG so close he thought he would hit him with his nose. He backed off to point blank range...about 10 feet...and on the deck. Gunsight or no gunsight, he couldn't miss. But each time he fired, the '86 would stall out due to the extremely tight turn and the vibration of the guns. Parr would then have to work his way back through the MiG's jet wash and into position.

On the fourth or fifth burst, Parr's fighter was soaked with fuel as he again stalled through the turn. The next short burst resulted in flame streaming from the MiG back around both sides of the F-86 and over the canopy. Then the MiG's engine quit. The Sabre shot past as the bandit hit the ground. Parr rolled into a left turn just as a MiG closed in steeply from the left. An immediate overshoot allowed Ralph to reverse....he simply held the trigger down and walked the tracers through before the MiG could get out of range. looking rapidly to his rear again, Parr saw five MiGs trying to cut inside him. A hard left turn kept them at bay, but he was being hosed with cannon fire as each MiG started shooting..."There were five of them firing at me and coming close!" Shooting at anything in front of him as he turned and maneuvered, flat on the deck, Ralph caused another MiG to hit the ground and explode. Whether from gunfire or not Ralph wasn't sure. But the others gave up and broke toward the Yalu as Al Cox showed up.

Both Sabres turned for K-14 (Kimpo) at extreme minimum fuel. Incredibly, throughout this engagement, Parr's Sabre sustained no damage, in spite of the fact that up to seven MiGs literally emptied their guns at him. After assessment of the gun camera film and Cox's account of the battle, Ralph Parr was given credit for two Migs destroyed and one damaged.

Parr's record in Korea stands as one of the most remarkable, a testimony to what agressiveness in combat means. Ralph Parr finished his Sabre fighter tour in Korea with ten victories, a total equaled by only ten other Korean War fighter pilots. Re made all of his kills in a span of 30 missions during the last seven weeks of the war, a time span no other Korean War ace was able to equal.

Col. Ralph Parr's full military

career spanned 34 years and three wars, giving him a total of 641 combat missions,

including two tours and 427 missions in Vietnam. With over 60 American and

foreign decorations, Col. Parr has the further distinction of being the only

man ever to be awarded both the Distinguished Service Cross and its successor,

the Air Force Cross - the nation's second highest decoration for valor.

The 330th FIF flew F-86Fs out of Stewart AFB, New York, iin the 1954-1955 time frame., before transitioning into the F-86D all-weather interceptor. (Credit- J.R. But' Conti.

SYLVIA TWO THREE

by John Powell

My home in Bucks County, Pennsylvania,

is near the Willow Grove NAS. As I passed the base a few weeks ago, I noticed

two old 'friends' from my USAF past. There on display were an F-80 Shooting

Star and an F-86 Sabre. I couldn't pass without stopping to get reacquainted

with those beautiful old fighters. As I sat on the bench in front of them,

my thoughts took me back to the early 1950s, shortly after the Korean War

ended. I had just been assigned to the 330th Fighter Interceptor Squadron

at Stewart AFB in Newburgh, New York. This was a lovely place to be after

eighteen months in pilot training and all-weather interceptor schools. During

pilot training, I had become very proficient in flying the F-80, an aircraft

I dearly love to this day. I developed complete confidence in its ability

to get me home, and it always did - even through two dead stick landings.

The 330th FIS was the only fighter unit at Stewart AFB, and we fighter pilots

were looked upon as akin to football stars or 'jocks', a status completely

new to me. There at Stewart, my USAF wings gave me instant recognition as

a real, live jet pilot, during the days when jets were new and thrilling,

always drawing crowds of onlookers.

After six months at Stewart, we were being re-equipped with F-86s, as they were returned from Korea. These were not new aircraft, but were somewhat tired and combat-worn. At first, I didn't think they were as 'user friendly' as my beloved F-80. I loved the '80 as one loves a beautiful mistress - and she loved me. She had always taken care of me. Because of this, I volunteered to ferry our F-80s to the Air National Guard units which were picking them up. Finally, however, "we ran out of F80s, and I had to make friends with the famous 'MiGKiller' of Korea, the F-86P - the glamorous lady starring in all the war movies from Hollywood. As 1 transitioned into the Sabre, I found it much more comfortable than the '80. The cockpit was spacious and well designed for my 6'2" frame.

The 330th shared its aircraft with senior officers assigned to headquarters, Eastern Air Defense Force, which was located on the hill above the flight line. Most of these officers were of WW2 and Korean vintage, fresh from the latest war and now assigned to desk duties, which they disliked but recognized as essential to advancement. One of these was a lieutenant colonel named Robin Olds, an ace in WW2 and married to a movie star. He would later become the only pilot to score victories In both WW2 and Vietnam (12 in WW2 and 4 in Vietnam). He loved flying, and had put out the word that he would buy steak dinners for any pilot and his lady IF the pilot could shake him off his tail when Olds 'bounced' him.

I thought I was as good as most of my squadron in the role of aggressor or evader, and needless to say, even without the diner offer, to 'wax' such a formidable foe would be a feather in any pilot's cap. Then, one crisp February day, as I was flying an P-86 at 25,000 feet practicing my assigned aerobatics and feeling in love with the sky and my ability to fly, I felt quite alone with the deep blue above and the pure white clouds below. The F-86 and I were becoming real friends! Just as I entered my last maneuver I became aware of another '86 right on my tail! Unfortunately, with my limited experience in the F-86, I had lots to learn about swept wing flying characteristics and slats. I was pulling far more 'g' forces than I had ever done before, and was careless about keeping the aircraft from yawing while turning. My old friend the F-80, was very forgiving about uncoordinated flight I had been told by the operations officer that in uncoordinated flight during high 'g' loads, the slats on the F-86 might not operate together. One might extend while the other remained closed, producing some very unexpected and nasty results. If this happened, I was to 'unload' the g's, which would reduce the angle of attack and result in a return to more or less normal flight conditions. This had never happened to me, so I forgot all about it in my effort to get Jumping Jack off my tail.

I was determined to do this, however, and as a last resort I extended my speed brakes and reduced power to idle, hoping he would fly right under and past me as I pulled up into a vertical position. When the aircraft had slowed almost to a stall, I retracted the brakes and applied hard left rudder to execute a 'wing-over'. As I did so, I checked my six o'clock and observed Jumping Jack still on my tail!

Suddenly I felt my Sabre enter a violent maneuver such as I had never experienced. The nose began swinging around in a wild circle, and I saw earth and sky rapidly changing places. All sorts of debris from the cockpit floor was floating around. I was bewildered and frightened, and might have bailed out, except that I figured the gyrations might preclude a successful ejection. I was headed for the ground - fast - and had just about given up hope of recovery. Then I heard, "Two Three, extend your speed brakes, advance your power to 100%, and neutralize your controls."

It was Jumping Jack, and his voice reassured me. Following his directions, the cartwheeling stoped, and the landscape (much to close now) settled down. I was under 5,000 feet, and Juming Jack calmly said, "Reduce your power and start a 3 ' G' pullout!" I did, and soon resumed level flight - an older but wiser fighter pilot. Jumping Jack got landing clearance for the two of us and suggested I write up the aircraft for an "over G" inspection.

After landing, I sat in the pilots lounge, drank a Coke, and tried to assess all that had happened to me that day. Jumping Jack had been the spokesman, but it was Divine intervention that had saved me, I felt sincerely. I was just about to go home for the evening when I was told that our CO wanted everyone to report to the Officer's Club at 1730 hours. I wanted to call my wife to let her know I'd be late but there was no time and I headed for the club.

When I arrived with three of my buddies, we were directed to a large private dining room. As we entered, my entire squadron came to attention. And our CO introduced me to Lieutenant Colonel Robin Olds and Mrs. Olds. Next to Mrs. Olds sat my wife of six months wearing a million dollar grin. As I was ushered to a seat beside my wife, Colonel Olds called for a toast: "A toast to First Lieutenant John Powell, the first pilot in this group to ouffly me and shake me off his tail!" Modestly, he continued that it was not the first time he had been bested, and probably not his last. But because I had so little time in the '86, 1 had earned the promised steak dinner. As my squadron mates congratulated me with applause, cat-calls, and whistles, I noticed that I had once again taken on the demeanor of an ice-cool jet fighter pilot. Inside of me, however, I knew there was a frightened young pilot who had almost 'bought it', but for the sake of God and Robin Olds.

Back at Willow Grove, with nostalgia

sweeping over me, I realized that over forty years had passed. I recalled

feelings long forgotten. And as my eyes filled with mist, my right hand formed

a fist, and I beat softly on my arm rest. "Ah God, if I could only fly

one of those magnificent machines again." And with that wish, "Sylvia

Two Three" slipped back into my memory once again.

GETTING THE "L" HOME

by the late Neil Fossum

In December 1956, I was a junior first balloon flying F-86Ds at Tyndall AFB

in Florida. I was getting plenty of flying, fishing and golfing. And yes,

my wife was eight months pregnant About the middle of the month, my boss asked

if I would fly to Fresno, California to ferry our first F-86L back. I told

him my wife was expecting within a month. But he assured me I would be home

for Christmas. As my bride was not having any problems, I agreed to go.

The next day I was asked by maintenance to ferry one of their F-86Ds, a hangar queen, out to Fresno so North American could modify the bird into an 'L'. I agreed and they worked day and night to make the airplane flyable. I gave it a test hop on December 18th. Right after takeoff, when I retracted the flaps, the bird started rolling to the left I pulled some power off and put the flaps back down in a takeoff position. After gaining a little altitude I discovered three things: first, the flaps were not coming up on both sides; second, the airplane would not fly with its wings level above 200 knots; and finally, I was not going anywhere in this beast in that condition! Maintenance jumped on it after I landed, and the next day I started my ferry flight with my first refueling stop at Greenville, Mississippi.

While getting lunch in Greenville and working out my next leg, the weather rolled in and the field dropped below minimums. The next day the weather was still lousy, but I think they were tired of my hanging around Base Ops and they temporaily jacked up the ceiling and let me go. Clearance delivery gave me an awfully complicated departure with several crossing restrictions. But after figuring out where they were, I cranked her up and called for taxi instructions. I went on the gauges immediately after takeoff. At 500 feet I was informed of two things: one, Greenville had again gone below minimums; and two, if I continued my flight I would be under violation! I asked them what the problem was and they calmly informed me that Flight Services said I had insufficient fuel to reach my destination at Big Spring, Texas.

The weather was bad to the west but I remembered that Dyess was forecast to improve. I informed Flight Services that Dyess AFB was my new destination. That satisfied Greenville, but when I approached Dyess they informed me that Big Spring was VFR and I landed there as planned. A check with the Airdrome Officer to see if a violation had been filed (or if the flying evaluation board had convened and was waiting for me) revealed I had not violated any rules. So I gassed up and headed for George AFB, with another fuel stop at Tucson.

It was great to get into the BOQ at George and then hit the club. After a tough day I was looking forward to some rest before heading to Fresno the next day. Next morning, December 21st, I arrived at Ops only to learn that the whole San Joaquin Valley was socked in and Fresno would be below minimums all day. By the next day, the 22nd, the weather at Fresno came up a bit and I snuck in that afternoon - at last! The troops at North American told me that my F-86L would be ready by 1000 hours the next day. But it was closer to 1230 hours before I finally got airborne.

One of the strange things about this particular F-86L was that its gear would not retract So after burning out some fuel for about thirty minutes, [landed back at Fresno and returned the 'L' to North American. Rather than carry my chute, helmet, and flashlight around, I left them in the cockpit. The North American people started working on the bird. They finally had it ready on Christmas Day and 1 took off about noon. By now my attitude needed a major adjustment as my clean clothes had long been depleted, as well as most of the contents of my wallet I was concerned about my wife and it WAS Christmas Day!

I filed a flight plan for George AFB as they had maintenance if I needed it. During the flight my attitude did not improve because when I engaged the autopilot I immediately got my head banged against the canopy! The autopilot wanted to do rolls all the way to George! I also noticed my oxygen was leaking at a rate of about 200 pounds per hour. At George I didn't mention any of these problems, nor the leaks that I saw. It was time to get the 'L' home, and I didn't want any delays because of a few stupid oxygen, fuel, and hydraulic leaks!

After refueling, I filed a flight plan for Big Spring with a stop for more fuel and oxygen. Departing Big Springs my takeoff roll seemed much longer than usual. But the bird finally started flying. I pulled the gear up and moved the flap handle to the 'up' position. But my flaps were already up! I had forgotten to place them in the takeoff position. It was now sundown and it had already been a long day. But at least I knew now why my takeoff roll had been so long. I made a mental note to be more careful and continued on to Alexandria AFB, Louisiana. While I was gping by Ardmore, Oklahoma I made a position report. Because it was Christmas night, and almost everyone was where they wanted to be, I had not heard any radio chatter for about thirty minutes. When Ardmore Radio called with a current altimeter setting, the operator was slurring his words so badly I could not understand him. I just replied - "Roger. It sounds like you're having a little party!" He replied -"Yeah, ha, ha! We've made a few trips to the parking lot!" I said - "Well, have one for me!", and he replied "Yeah, OK!" A few seconds later I received a very clear, very sober transmission with a current altimeter setting. I suspect the Ardmore boss overheard our conversation as his voice sounded more than a little agitated.

By the time I landed at Alexandria, my Sabre didn't have enough oxygen left to keep a canary alive. But there was only one short leg left so I didn't mention it. I also noticed that my flashlight was missing. It was probably at Presno in someone's tool box.

There was a Major on duty in Base Ops at Alexandria. He was in a really foul mood, probably because it was Christmas and he was stuck with A.O. duty. Because I did not have my own clearing authority, and I was a First Leutenant, I treated him with kid gloves. When I placed my flight plan on the counter for his signature, he said - "You're ferrying this airplane, aren't you?" I said "Yes Sir!" He said "You're not supposed to ferry a plane at night or in weather, are you?" He was correct on both counts. I then said " You're not going to Stop me, are you?" He replied "You're not going to crash on my airdrome, are you?" I quickly said "No Sir!". He looked at me for a moment, signed my flight plan, and I was out the door.

On the way out I turned to the Major and asked if he knew where I could buy a flashlight? He said "You don't have a flashlight?" Realizing I had just goofed, I mumbled something about it being stolen, but all my cockpit lights were working OK. As I walked out I heard him say - "I've heard about all I want to hear about this flight --!"

When I arrived at transient alert, the buck sergeant informed me that I had a severe oxygen leak, which had lost 200 pounds since he had topped it off. I said "That's OK. But I would appreciate it if you would top it off again after I crank her up." He looked at me a little strange but said "OK".

After getting clearance, I fired the engine up. About this time a Convair twin-engine landed - maybe a Southern Airlines bird. I didn't think anything about it. Finally, the sergeant topped off the oxygen, pulled the wheel chocks, and the tower cleared me to taxi.

As I approached the active runway, the tower asked if l was going to use the afterburner for takeoff?. I replied I hadn't planned on it because of its high fuel consumption and I was flying all the way to Tyndall on this leg. When I asked why, he said the two commercial pilots in the Convair had seen me getting ready to go and had stopped in the tower to watch my afterburner. As it was a very black night in that part of Louisiana, and the flame pattern from my afterburner was so obnoxious, I said "Sure. I'll plug it in!" The tower cleared me for takeoff. As my speed rapidly increased I decided to give them a max performance takeoff. While I was at it, I held the Sabre down until I thought the tire treads.would peel off! Then I rotated her and sucked up the gear.

I was looking into a black hole with no stars, no clouds, and no city lights. My artificial horizon at the bottom of the instruments was of no use at all. Looking out over the canopy rails provided no clue as to my altitude. It was as black as a Louisiana swamp! My airspeed held at 140 knots. I couldn't get it out of 'burner until I got the nose down. So my only course was to ease the stick forward. As soon as the artificial horizon provided some useful information I pulled it out of afterburner.

At this point I had scared myself, and my knees were shaking. Realizing that my voice would probably be several octaves higher than normal, I conciously lowered it and asked the tower - "How did they like that?" The answer was - "They loved it and wished they could change jobs with you!" After considering this entire trip and the headaches, I replied "I might be talked into that about now!"

After landing at Tyndall I parked, filled out the log, left my chute and helmet in the cockpit, closed the canopy and went home. My wife was fine. But Christmas Day was long gone. She asked how it went and I replied "It went all right." Now she knows the truth becuase she typed this!

Two months later a Captain Howard

flew the second F86L into Tyndall. The base photographers took pictures, and

he arranged for a nice article in our base newspaper about how he flew the

first F-86L into Tyndall. Oh well! Anyway, it was nice to get the 'L' home!

A LETTER HOME

l/LT Donald L MacGregor Jr.

51st FIW 25th FIS

K-13 Suwon, Korea

August 12,1953

Dear Family,

Now that you all know that I had to bail out of an F-86 Sabre Jet on the last day of the war, I will fill you in on all the details. I thought it would worry Mother too much if she found out about the incident, and that's why I sent a short note to Dad at the office after being rescued and very briefly told him what had happened in case the story got in the newspaper or somehow you heard about it. In that event you would know I was aliright from the letter I wrote to Dad. But now that you have been informed, which is what I probably should have done in the first place, I will try to fill in all the details that I left out in the letter to Dad.

On July 27th, the Korean truce was signed. The truce, among other things, called for a twelve hour grace period when a physical count of all aircraft on both sides was supposed to be made by some sort of neutral commission. After that no more aircraft would be allowed into Korea by either side. This caused our side quite a problem since most of our major maintenance was done in Japan, and we had a lot of aircraft over there. Consequently, we had to get those aircraft back into Korea that night.

Our squadron was scheduled to fly missions that day to help prevent the communists from bringing in aircraft and other items that were never in Korea, and as it turned out, that's exactly what they tried to do. Every pilot in the squadron wanted to fly a mission that day because we thought, now that the war was over, the number of missions each of us had flown, would determine when we could go home. In "A" Flight, the way we decided who would fly a mission or who would go to Japan to fly one of our aircraft back to Korea, was by flipping a coin. I flipped a coin with my good friend, Julius "LW" Regeler, from Danville, Illinois, and Julius won the mission, and I got the trip to Japan.

When we landed at our maintenance base in Japan, things looked pretty hectic on the flightime because the maintenance people were racing the clock to get our aircraft ready for flight. My F-86 was finally ready, after an engine change and when my flight plan had been filed and cleared, I departed for Korea at seven p.m. which was about an hour before dark. Everything appeared normal as I climbed on course to 21,000 feet where I leveled off. Usually we climb to around 40,000 feet for better fuel consumption, but on this particular flight, I didn't have far to go and decided I would have plenty of fuel for the trip at that altitude. It's probably a lucky thing that I did decide to cruise at that lower altitude since at higher altitudes bailouts are far more dangerous due to a lack of oxygen and extremely cold temperatures.

My first indication of trouble was an engine vibration lasting only a few seconds. On checking my engine instruments, I saw I had no oil pressure. I knew I had a serious problem, and decided to land at the nearest suitable field in Korea which was located near the town of Pusan, on the southern tip of Korea. Next, I contacted the tower at Pusan, advising them of my problem and told them would keep them posted on my progress. I took up a heading to Pusan and had just tuned in the Pusan homer on my radio compass when I noticed that my tailpipe temperature was increasing and my engine rpm's were decreasing. This indicates an engine seizure, and I knew I was now in real trouble. In a few seconds, I felt an explosion in the engine compartment behind me, and at that moment, the aircraft began to vibrate as though it would shake itself to pieces. Then the fire warning light came on indicating an engine fire, and the cockpit began filling up with smoke. I quickly turned my oxygen to 100%, so I wouldn't be overcome by smoke. It was pretty obvious by now that the airplane and I would soon part company. The next step was to advise Pusan that I was planning to bail out so they could take a fix on my position and alert Air Sea Rescue. I began preparations to eject from the aircraft. First, I unfastened the navigation log from my leg, lowered the windblast shield on my helmet over my face, leaned forward to prevent the canopy from hitting me in the head, and pulled the lever that blew the canopy off the aircraft. I figure I was traveling at a true air speed of around.560 miles per hour, without a canopy, so you can probably imagine the windblast that hit me as I sat erect in the seat to eject. As soon as I felt I was sitting correctly in the seat, I squeezed the trigger on the seat which violently shot me out and over the top of the aircraft. I might add here, that both the seat and the canopy are equipped with powerful explosive charges which make high speed bailouts possible, and needless to say, it is quite a boot in the pants when the seat fires. At any rate, it may sound that this sequence of events covered a long period of time. Actually, from the time I experienced the first vibration, until I ejected, was no more than a very few minutes.

After leaving the aircraft, my helmet and oxygen mask were torn off my head, and I began to tumble over and over, backwards. Due to the altitude and very cold temperature, I decided to free fall down to a lower altitude where it wouldn't be so cold and where there would be plenty of oxygen. Here is where I made my first mistake which probably should have cost me my life -- I forgot to unfasten the seat which was still strapped to me. I guess was so intent on watching a rock out-cropping in the ocean to give me some idea how high I was and when to pull the rip cord, that getting rid of the seat never crossed my mind. When I felt I had lost sufficient altitude, I tucked in my chin, put my feet together and pulled the rip cord. The chute opened with quite a jolt since the heavy seat was still attached to me. As soon as the chute was fully opened, I noticed that many of the panels had been ripped out. I noticed for the first time that I was still sitting in the seat, and so, I unfastened my seat belt and watched the seat fall away toward the ocean. I looked at my watch in order to time my descent, but it had stopped due, I imagine, to either the opening shock of the parachute or probably the jolt of the ejection seat.

I was pretty happy to be alive after all that, but I still wasn't safely on the ground. I began to look around to see where I was going to land. I noticed that I was over the coast of an island but the wind was carrying me out quite a bit, but was probably for the best since the island was very hilly and covered with trees which might have caused some broken bones on landing. I could see several small boats below me, and I felt certain they could see my parachute and would come to my rescue when I landed in the water. However, the wind was carrying me farther and farther away from the boats.

At first, the descent in the parachute was rather enjoyable. I had no sensation of descending at all. In fact, I felt as though I was suspended in mid-air. But, about the time I got comfortable, the chute bgan to swing me from side to side, and I was certain the chute would collapse. It continued to oscillate periodically during the rest of the descent, and at times, I would swing almost parallel with the canopy, which would momentarily start to collapse. But, the badly torn chute managed to stay open in fine shape all the way down.

Since I have the additional duty as personal equipment officer of the squadron, I am pretty well acquainted with all the emergency equipment I had been sent to a course on the use and maintenance of emergency equipment, and I often was called on to give briefings on the subject to pilots in the squadron; so, there wasn't much doubt in my mind as to how to make a water landing, using some of my own techniques as well as standard operating procedures. While I was still descending in the chute, I slid back in the sling and unfastened all the harness straps so that I would be able to get free of the chute simply by raising my arms when my feet touched the water. Next, I partially inflated the rubber raft and mae west. As soon as my feet hit the water, I released from the parachute harness and was free of the chute. Since the dinghy was attached to me, it was floating right beside me, and it was easy to pull myself into the raft. After I was in the raft, I fully inflated the raft and mae west. The procedure worked so weli that I didn't even get my hair wet and was in the water for only a matter of seconds.

The ocean swells were fairly high, cutting down on lateral visibility and making it impossible to see any of the small boats that I had seen on the way down. I used one of my signal flares, that I carried with me, to attract their attention, but I still didn't see any boats. By this time it-was dark, and it looked as though I would have to spend the night at sea in my little rubber raft I had quite a lot of survival equipment with me and a few more flares to attract the attention of any rescue parties that I felt certain were already on the way. So, while I was a little concerned about my situation, I was confident I would survive.

About an hour later, I saw a light bobbing up and down off in the distance and fired off the rest of my flares. As the light moved closer, I fired my 45 pistol a few times to attract attention, and in a short time I was on board a small fishing boat The crew spoke no english and were dressed in striped T shirts, looking right out of "Terry and the Pirates". I sat in the bow of the boat under a light and without being conspicuous, kept mypistol ready to fire.

After about an hours ride, we landed at the little fishing village of Izuhara on Tsushima Island. The whole village was waiting on the dock when we landed, all talking excitedly in Japanese. The editor of the village newspaper was the only one that spoke even a little English, and I managed to ask him if by any chance were there any Americans on the island. He said there were and that he would contact them. While he was off looking for the Americans, I began to think of something I could give the fisherman for picking me up.I decided the only thing I had of value was the nylon canopy of the parachute which they seemed overjoyed to receive. I was becoming somewhat embarrassed with all the villagers staring at me as though I was from another planet, and I was relieved when an army jeep appeared on the dock. An army lieutenant stepped out of the jeep, introduced himself, and told me my plane had crashed next to the last house in the village, scaring the town half to death. He thought I had landed on the island and had been searching the island ever since the plane crashed. It struck me as ironic, that with all that open ocean, not only did the plane hit the only island, but also the small village on the island. I was very thankful that no one in the village was killed or injured.

Air Sea Rescue had arrived on the scene by this time and were dropping very bright flares out in the ocean hoping to spot me. I contacted the plane with an army radio and told them I was on dry land and asked them to send either a boat or chopper to pick me up the next day. The army lieutenant took me to the crash scene which was nothing more than a large hole in the ground filled with water at the bottom as if it had been a bomb instead of an airplane. What was left of the aircraft was scattered in a million small pieces in a large radius around the crash scene.

The army lieutenant is in charge of a signal corps detachment consisting of eleven soldiers and has the best duty I've ever seen. The army has taken over a beautlful fuedal estate overlooking the harbor, and he eats like a king in a private dining room. The other day I received a letter from him inviting me to spend a few days on the island during my next R&R; which I may do, if we ever get any more R&R;'s.

The next afternoon a PT boat, converted to rescue service, arrived to take me back to Korea. I had hoped to spend a few days on the pretty little island and hated to leave but I had no choice in the matter. Also, now that the war was over, I really didn't want to spend any more time in Korea but instead would have preferred to spend the rest of my tour in Japan, possibly at our maintenance base. Anyway, hours later the PT boat dropped me off on a very dark dock at about eleven pm and told me I was on an airbase near Pusan. They backed out and left me standing there. I was awfully stiff and sore by now but managed to walk around until I found a building with some lights on which turned out to be the officers club. I was a little hesitant to go in because I didn't look so hot with a beard, ripped flight suit, and an open parachute on my back with the nylon cords hanging down where I had cut off the canopy. But, I did go in, and spotted a lieutenant colonel sitting at the bar. I told him what had happened and suggested that I was back in Korea illegally in view of the armistice and should be sent back to Japan. My request was denied, and the next day I found myself on board a C-1 19 bound for my base at Suwon.

A few days later I was sent back to Japan to meet with the accident investigation board. I felt very uncomfortable because they were not very friendly and from the line of questioning, they seemed to want to hang the cause of the accident on pilot error, meaning me. As of this writing, I haven't been told what conclusion the accident board reached, but I did hear from someone in the know, that maintenance had failed to put any oil in the engine after it was installed, but the board felt there was probably enough sludge in the system to give me at least a minimum oil pressure reading on takeoff. Well that's the whole story. Enclosed are two Japanese newspaper accounts of the crash along with translauons -- please hold on to them for me.

I hope to be home for Christmas, but will just have to wait and see what happens.

With love to all,

Don

NASM HONORS THE F-86

Welcome back, Sabre 260!

The F-86 Sabre Pilots Association is proud that the National Air and Space

Museum (NASM) has chosen an F-86A as the featured display of their "U.S.

Air Force 50th Anniversary" exhibition. The museum provided the following

press release:

"As a seperate military force, the US Air Force fought its first war in 1950 in Korea. Air power proved critical when North Korean forces swept into South Korea and US Air Force and Navy aircraft stemmed the tide. Later, the North American F-86A Sabre played a key role. Rugged, fast, and powered by a single turbojet engine, the Sabre quickly dominated its principal rival, the Soviet-built MiG-iS. Equipped with excellent handling characteristics, the Sabre could exceed the speed of sound in a shallow dive. During this conflict, Sabres destroyed almost 800 MiG-15s, while losing fewer than 80 of their own. The Sabre will be on display through May 5, 1997. It bears the markings of the 4th Fighter Wing (as used) during the period prior to June 1952."

This particular Sabre (#48-260) is familiar to many members of our association, having appeared ("NASMs F-86A-5") in the very first issue of Sabrejet Classics (vol 1, #1, Spring 1992). A reader discovered a personal photo showing #260 on the 335th Squadron flight line at K-13 (Suwon) in the spring of 1951, and the photo was published in our Fall 1992 issue. Ion Walter, an Associate Editor, recalls visiting NASMs. Garber Restoration Facility in 1980, and seeing #260 awaiting her finishing touches. Lon told the NASM guide that he had flown that aircraft, and when the guide asked "The F-86?", Ion replied, "Yes, and THAT VERY F-86!". Ion then explained the markings were incorrect for the time period, and soon provided NASM with color slides of correctly marked Sabres; It is believed that NASM used these slides to paint their restored F-86A.

Our Association takes great pride

as well, that one of our members, U.S. Representative Sam Johnson (R,Texas),

is now a member of the Board of Regents of The Smithsonian Institution. He

will be our featured speaker at the reunion banquet in April. The director

of NASM is Vice Admiral Don Engen, a three war Navy pilot who is well-versed

in the role played by air power in our nation's history. The "USAF 50"

exhibition is a credit not only to USAF and the Sabre, but to the Smithsonian

as well. It is a clear signn that the problems of the controversial ENOLA

GAY exhibit are not likely to be repeated. We urge our members to visit the

NASM to say Hello to our old friend, F-86A-5 #260.