At first the

thrown-together collection of mostly obsolescent planes seemed sufficient

to handle this new air war, quickly decimating the North Korean air

force. But the Americans got an unwelcome surprise on November 1 when

five Mikoyan Gurevich MiG-15s attacked a flight of North American

F-51 Mustangs. The enemy jets were flown by Soviet pilots based in

Manchuria who were secretly aiding the North Koreans. One week later

the world’s first all-jet air battle took place between the

aging American Shooting Stars and Soviet MiG-15s. Although one MiG

was claimed, it became obvious that the newer sweptwing MiG-15s outclassed

the older Shooting Stars, which couldn’t adequately protect

the B-29s. As Superfortress losses mounted, President Harry Truman

ordered an F-86A Sabrejet frontline unit, the 334th Fighter Interceptor

Squadron, to Korea.

In December

1950, Levesque—now a flight lieutenant—arrived in Korea

with the first Sabrejets. He would become the first Canadian to fly

air combat missions in the Korean War. The Sabre impressed Levesque:

“It was like being on a bucking bronco—I didn’t

ride it, I just hung on! It had lots of power and could turn on a

dime. When you pull back you get a whole lot of air—the stabilizer

doesn’t fight the elevator. This made the aircraft tremendous.”

He earned the U.S. Air Medal for flying 20 missions between December

17 and December 21, 1950, inclusive, an average of four missions a

day.

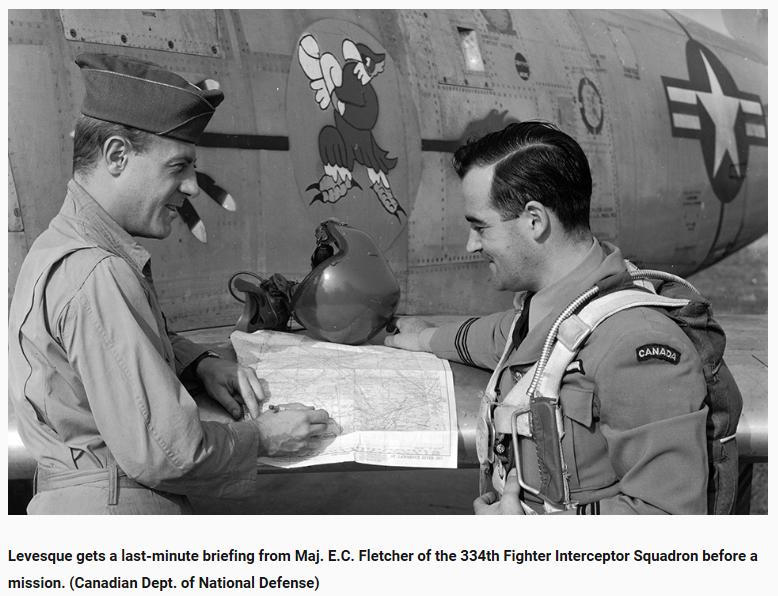

On March 31, 1951, Levesque was with two squadrons of Sabres protecting

a large flight of B-29s attacking the bridges spanning the Yalu River,

the boundary between North Korea and its Communist Chinese ally. He

was flying as wingman to Major E.C. Fletcher when suddenly the squad

leader called out that bandits were coming from the right. The Sabres

dropped their auxiliary fuel tanks as two additional MiGs were spotted

at 9 o’clock, “off our left wings and above us a bit.”

Levesque’s flight turned toward these two enemy planes, which

separated and banked away to evade the pursuing Sabres.

Levesque later

reported: “My MiG pulled up into the sun, probably trying to

lose me in the glare. This was an old trick the Germans used to like

to do—but this day I had dark sunglasses on, and I kept the

MiG in sight.” The MiG leveled off, likely not realizing Levesque

was still on his tail. The Canadian adjusted his illuminated gunsight

for deflection shooting and banked steeply to turn inside the MiG,

triggering a twisting dogfight that quickly spiraled down from 40,000

feet to 17,000 feet. Levesque was about 1,500 feet from the MiG when

he opened fire. His aim was good: Six streams of .50-caliber bullets

smashed into the MiG, which rolled violently to the right and continued

rolling until it crashed into the ground.

“I started

to pull up, and saw another MiG diving from above me,” he continued.

“I climbed into the sun at full throttle and started doing barrel

rolls. The MiG disappeared.” His combat with the MiGs concluded,

Levesque faced another danger, this time from friendly fire: “I

went right through the B-29 formation and they all shot at me! Thank

God they missed. I waggled my wings and they stopped firing, but lots

of shells had just missed me.”

Levesque suddenly

realized that his fuel was approaching “bingo,” the point

where he had just enough to get him back to base at Suwon, South Korea.

As he headed home, alone with his thoughts, he could take pride in

the fact that he was at last an ace.

Omer Levesque

was awarded the U.S. Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in the

March 31 battle. He would complete 71 operational sorties with the

334th FIS before being sent home in June 1951.

In addition

to his other decorations, Levesque received the Queen’s Coronation

Medal in 1953. Following a variety of peacetime assignments, he retired

from the RCAF in 1965. Inducted into the Quebec Air and Space Hall

of Fame, he served on the Canadian government’s Air Transport

Committee for 22 years, until 1987. Levesque died in June 2006, at

age 86.