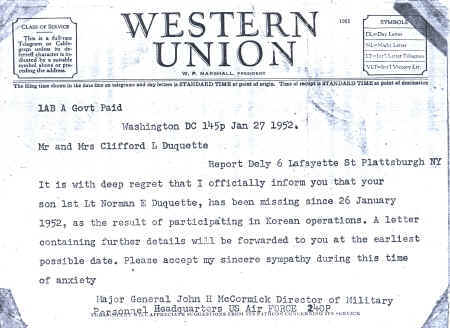

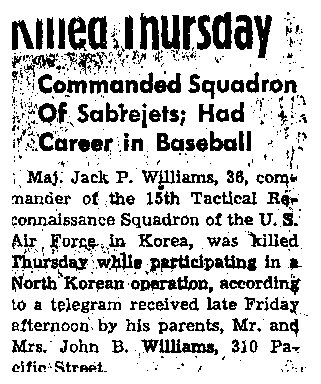

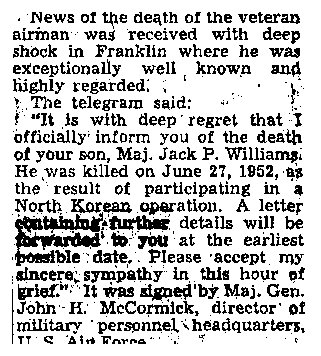

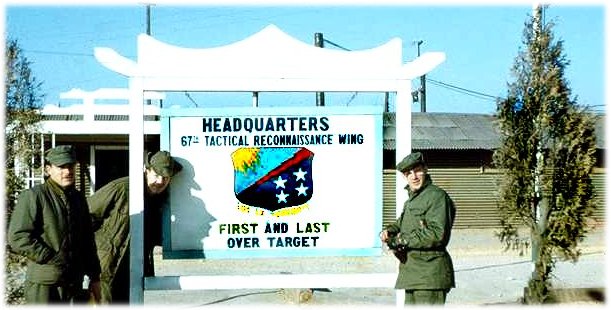

The Loss of

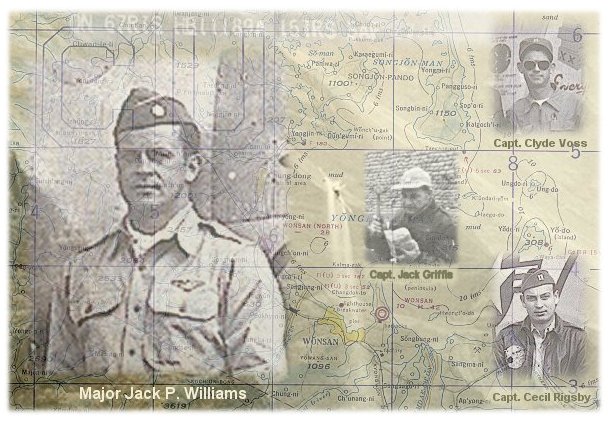

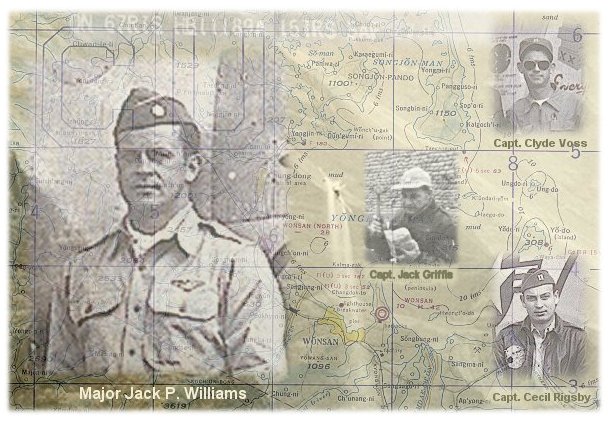

Major Jack P. Williams

Commander, 15th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron

by John N. Duquette

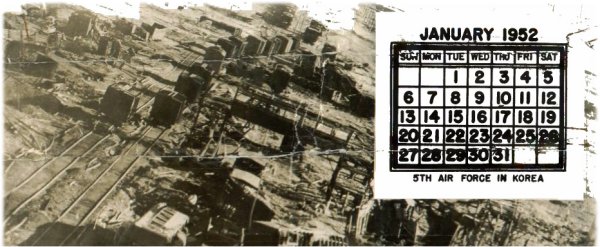

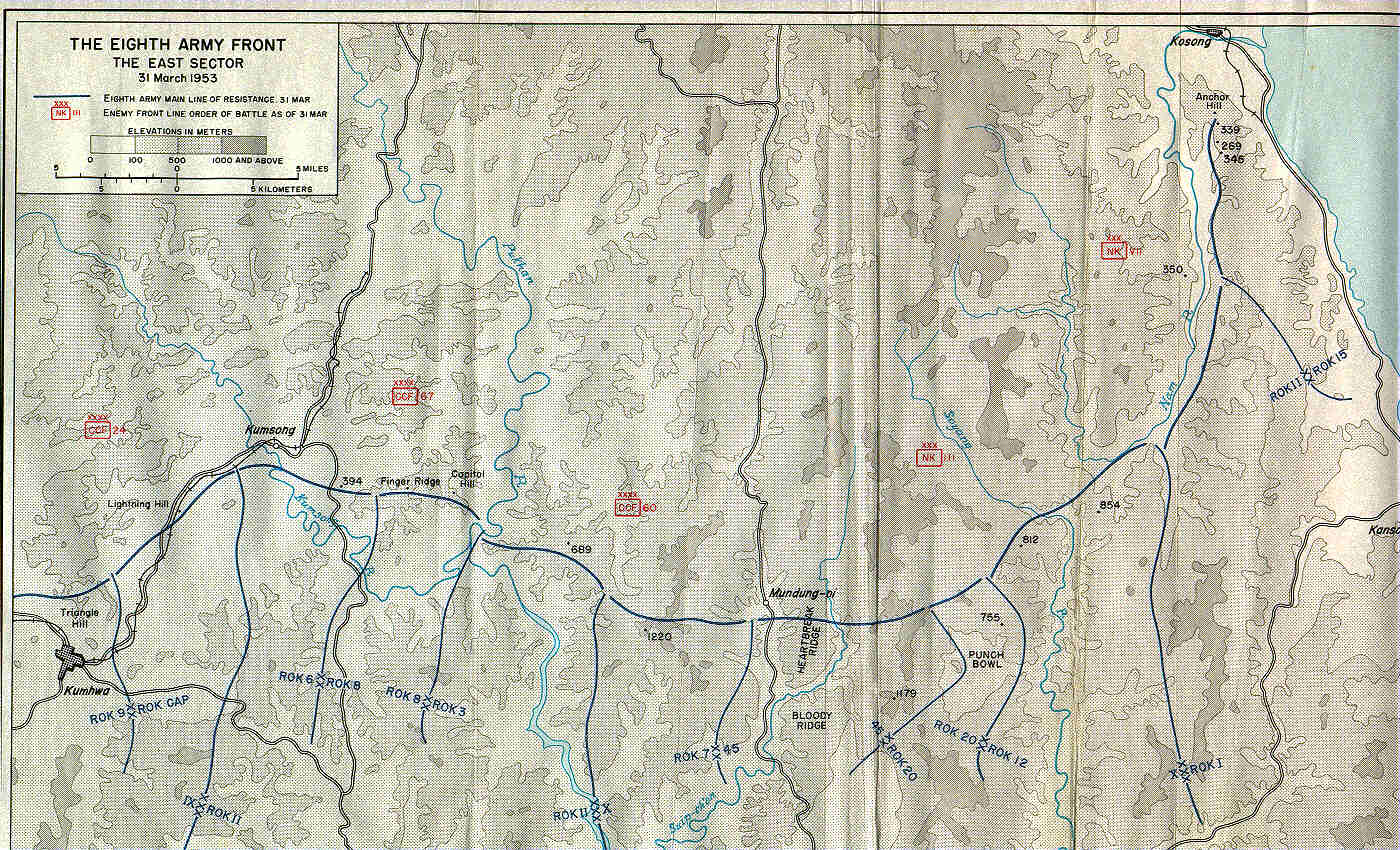

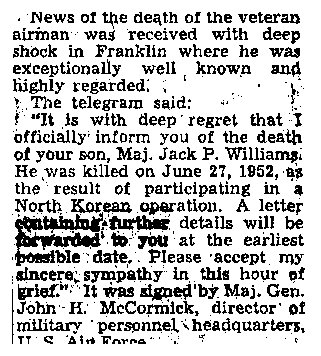

On 23 June

1952, the air forces of the United Nations Command launched a five-day

operation against the North Korean hydroelectric system. At the end

of five days and nights of air strikes, the electrical generating

capacity of North Korea had been reduced by 90%. Lieutenant General

Glenn O. Barcus, Commander, 5th Air Force called the operation “a

singular success”. He noted to his superiors that only two Navy

aircraft had been lost in the entire operation and that air search

and rescue units had recovered the pilots of these planes. Not included

in these statistics was the loss of a U.S. Air Force RF-86A and its

pilot, Major Jack P. Williams, Commanding Officer, 15th Tactical Reconnaissance

Squadron. This is the story of that operation and the circumstances

relating to the loss of Major Williams.

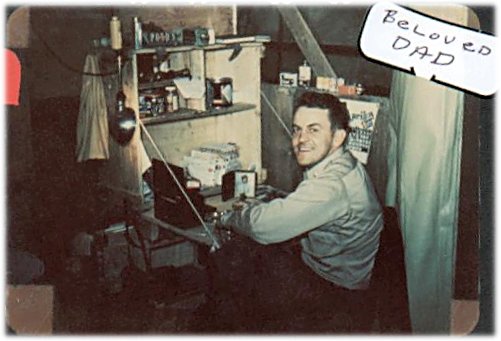

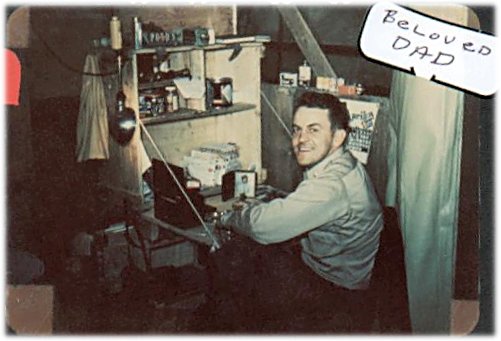

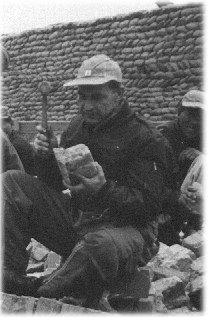

Major Jack Williams in his tent

Kimpo Airfield, Spring-Summer 1952

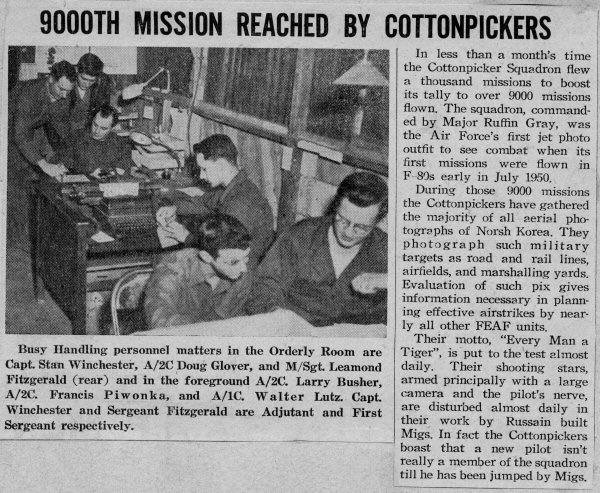

Spring 1952

Kimpo Airfield (K-14)

Republic of Korea

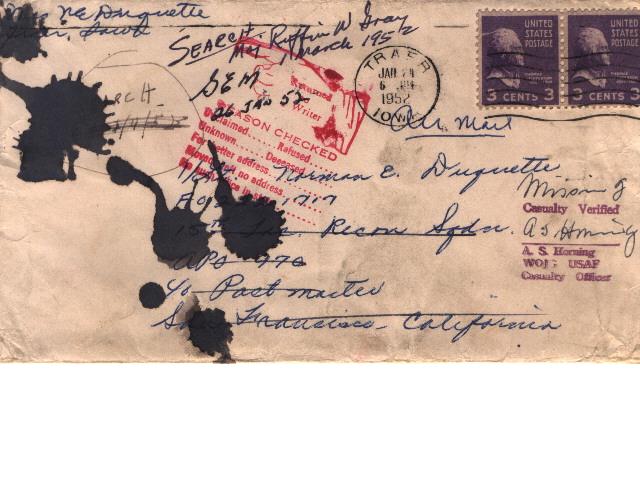

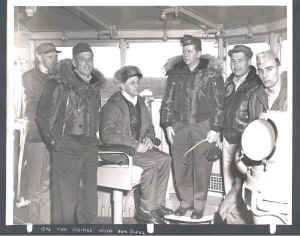

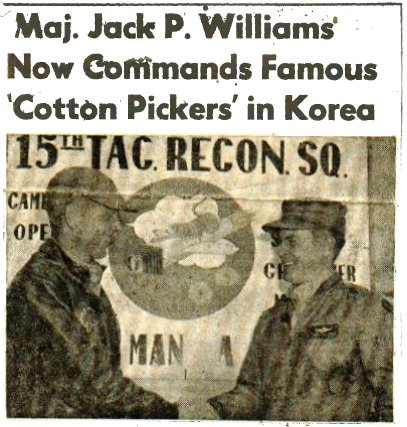

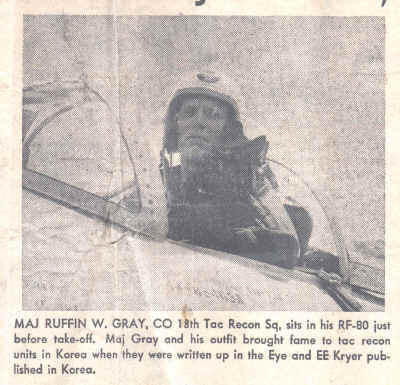

Maj. Ruff

Gray and Maj Jack Williams change command of the 15th TRSOn 16 April

1952, Major Ruffin W. Gray passed the command of the 15th Tactical

Reconnaissance Squadron (Photo Jet) to his tent mate Major Jack P.

Williams. Of the event Gray later wrote,

"I felt so keenly about the squadron that I absolutely refused

to relinquish command to just anyone; however, once I knew Jack, I

had no reluctance in turning it over to him--feeling, as I did it,

that the squadron would benefit by the change. What a wonderful leader

he was and what an outstanding example he set! The men and officers

all loved him." (1)

*****

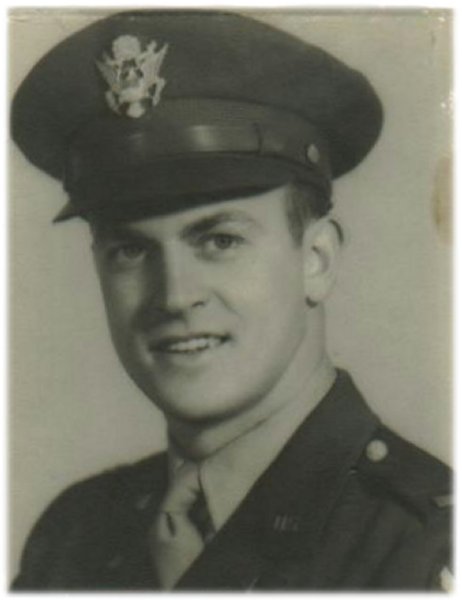

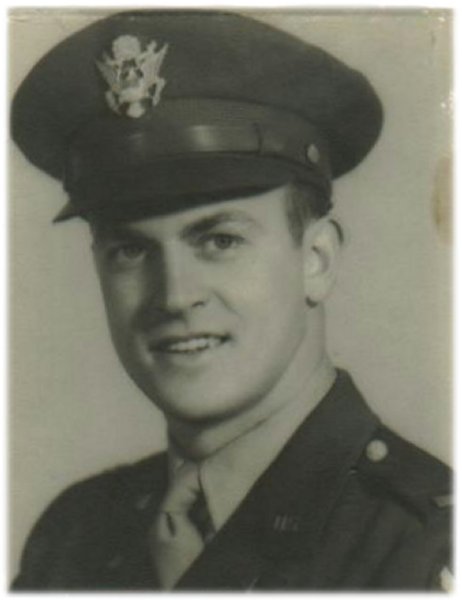

Lt. Jack Pryer

Williams, U.S. Army Air CorpsJack Pryer Williams enlisted in the Army

Air Corps in October 1941. He received his wings as a Second Lieutenant

on 3 June 1942. After serving as an instructor at Moody Field, Georgia;

Harding Field, Louisiana; and Henderson Field, Florida, Lieutenant

Williams was assigned to Adak in the Aleutian Islands in August, 1943.

Lt. Jack Williams flying a P-40 "Tomahawk"Between the Second

World War and the Korean War, Williams' duty stations included Biggs

AFB, in El Paso, Texas, where he attended the Staff and Command School.

He was also stationed at Greenville AFB, South Carolina, and Langley

AFB, Virginia. In December 1951, he and his family were at his parents’

home on Christmas leave when he received word of his assignment to

Korea. He shipped out almost immediately and arrived at Kimpo Airfield

shortly just after New Year's 1952 where he was assigned to the 15th

Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron. (2)

Despite his

11 years of service, this was Williams' first assignment to a tactical

reconnaissance unit. As such, he spent his first days in Korea getting

oriented to the terrain, the aircraft, the camera configurations,

and the photo-reconnaissance techniques used by this unique squadron.

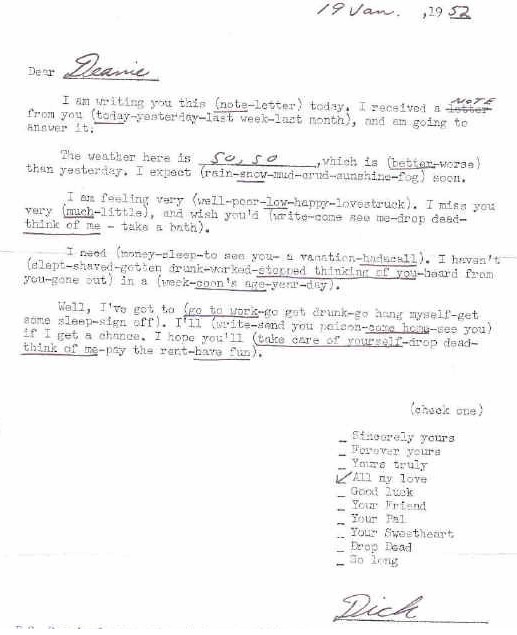

In a letter to his sister shortly after arriving in Korea, he captured

his initial impressions of the country and the reconnaissance mission

:

4 February

1952

Kimpo

Airdrome

Korea

Dear Wease,

Bill & Margie,

It has

been a bitter cold day today here at Kimpo (only time I really been

warm today was up flying this morning in an RF-80 [R for reconnaissance]

with a heater that really put out even though it must have been -40

degrees or so at 12,500 feet). We are located about 20 miles northwest

of Seoul, almost on the West Coast—not far from Inch’on

where, incidentally, you'd better watch out for our Navy shoots at

anything that flies overhead.

I am not

“operational” flying combat missions yet, but should be

soon. I have been flying practice photo missions and trying to learn

this recon business. We do visual and weather reconnaissance as well

as photo. The cameras (we can carry as many as five big ones in the

nose) are preset by our ground crews, so it's pretty much automatic

for the pilot. You have only five switches to work, plus flying the

plane, dodging Migs and flak. Seriously, however, most of the pilots’

concentration is required in getting his plane aligned with the target,

and flying at a constant airspeed and altitude while the cameras are

working…

…It's

been quite a mild winter in Korea thus far, so I’m told, &

it really hasn't been too bad since I've been here except for two

or three days. Korea is about the same size & shape as Florida,

but is rough and rocky like the territory west of Denver. The Koreans

are surprising people, and have intense national pride, despite the

fact that some nation has dominated them almost all their history.

They impress me more than the Japanese and have better farms, buildings

& factories. Hope this finds you all well and happy. Write me

when you can.

Love,

Jack (3)

*****

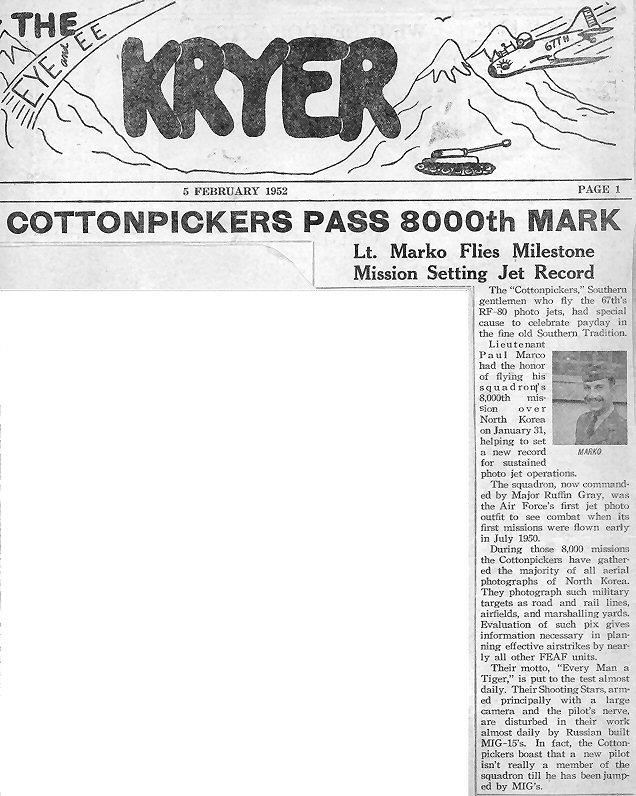

Williams'

first combat mission over North Korea came in early February 1952.

In late March, nearly a month and a half later, he took over as acting

commander of "The Cottonpickers" Squadron when Major Gray

received his assignment back to the States. After several weeks transition,

MAJ Gray departed and Williams became the commanding officer “on

his own” on April 16th.

On Sunday, June 15th, Williams wrote a letter home. In this letter,

he mentioned that he had been put in for "the oak leaves of the

lieutenant colonel’s rank which my job calls for". He noted

that his many administrative duties as squadron commander were very

time-consuming; “But I’m still trying to get in one mission

myself each day we’re flying.” (4) By

June 26th, 1952, Williams had flown 89 combat missions over North

Korea—all in RF-80 "Shooting Star" aircraft.

It was Air

Force policy that after flying 100 combat missions, pilots were rotated

back to the United States. By squadron tradition, the last ten of

these combat missions were “milk runs”—photo missions

that were the least dangerous of those needing to be flown. Williams

had one “sweat” and ten “no sweat” missions

to go. At his current rate of flying, he was expecting to be back

in the United States by the end of July.

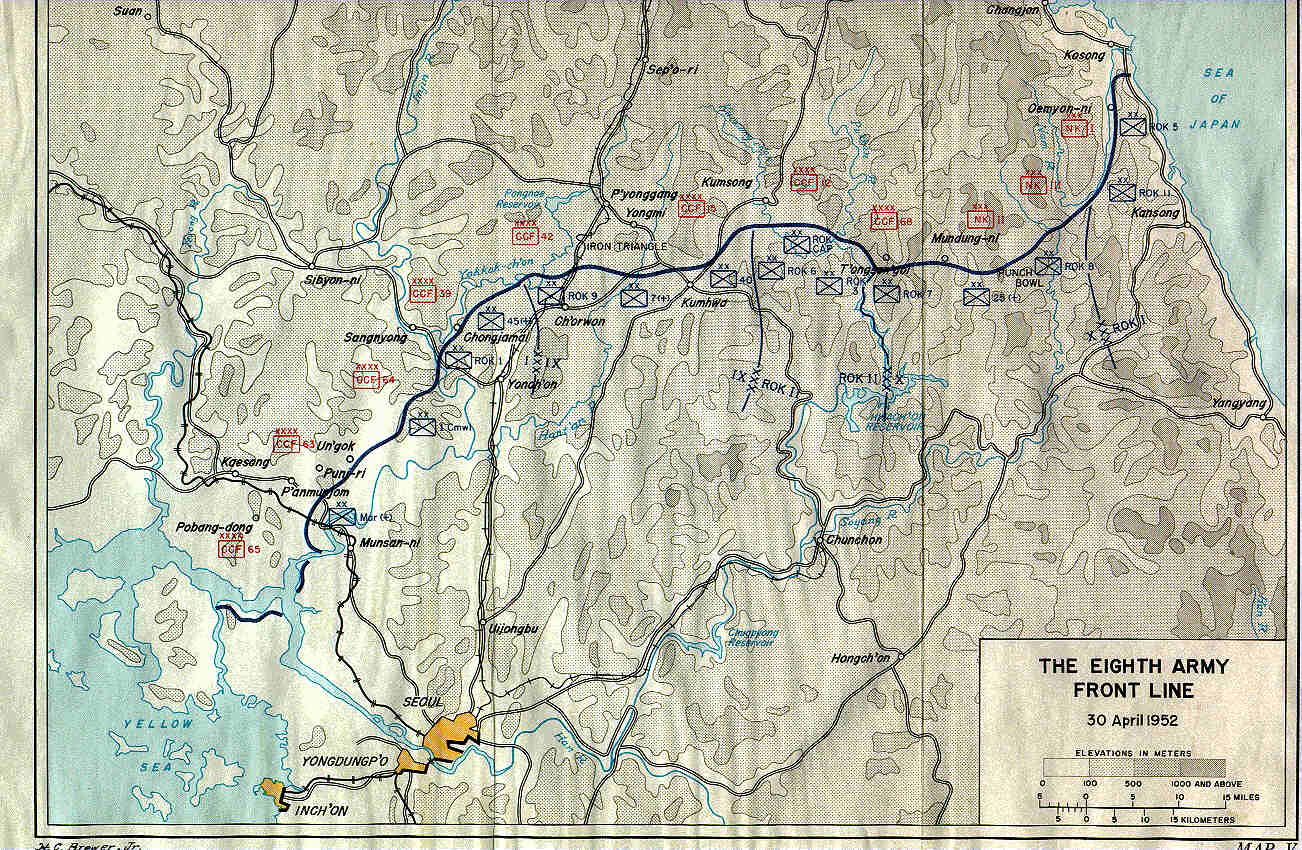

May 1952

Headquarters,

CINCUNC

Tokyo, Japan

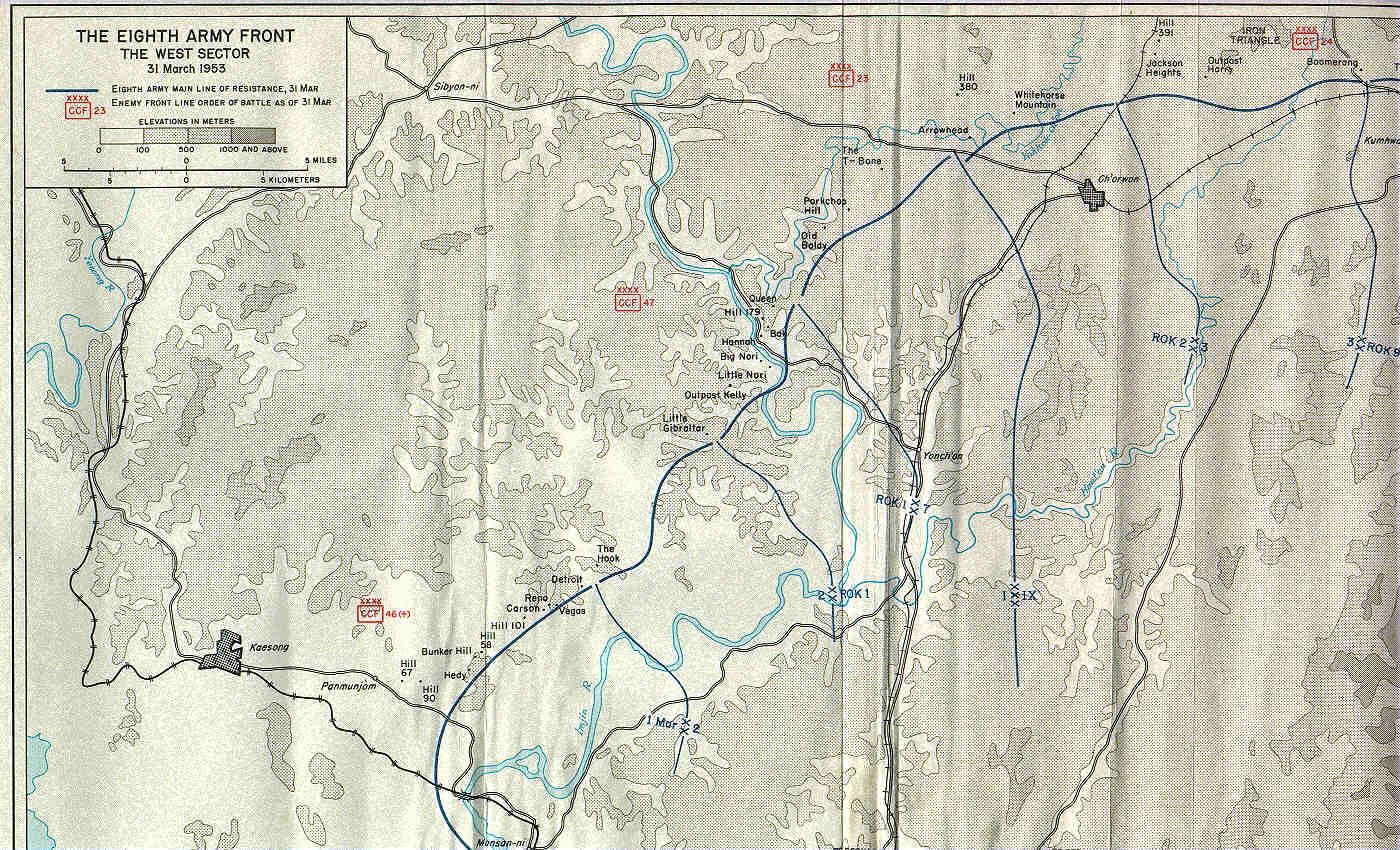

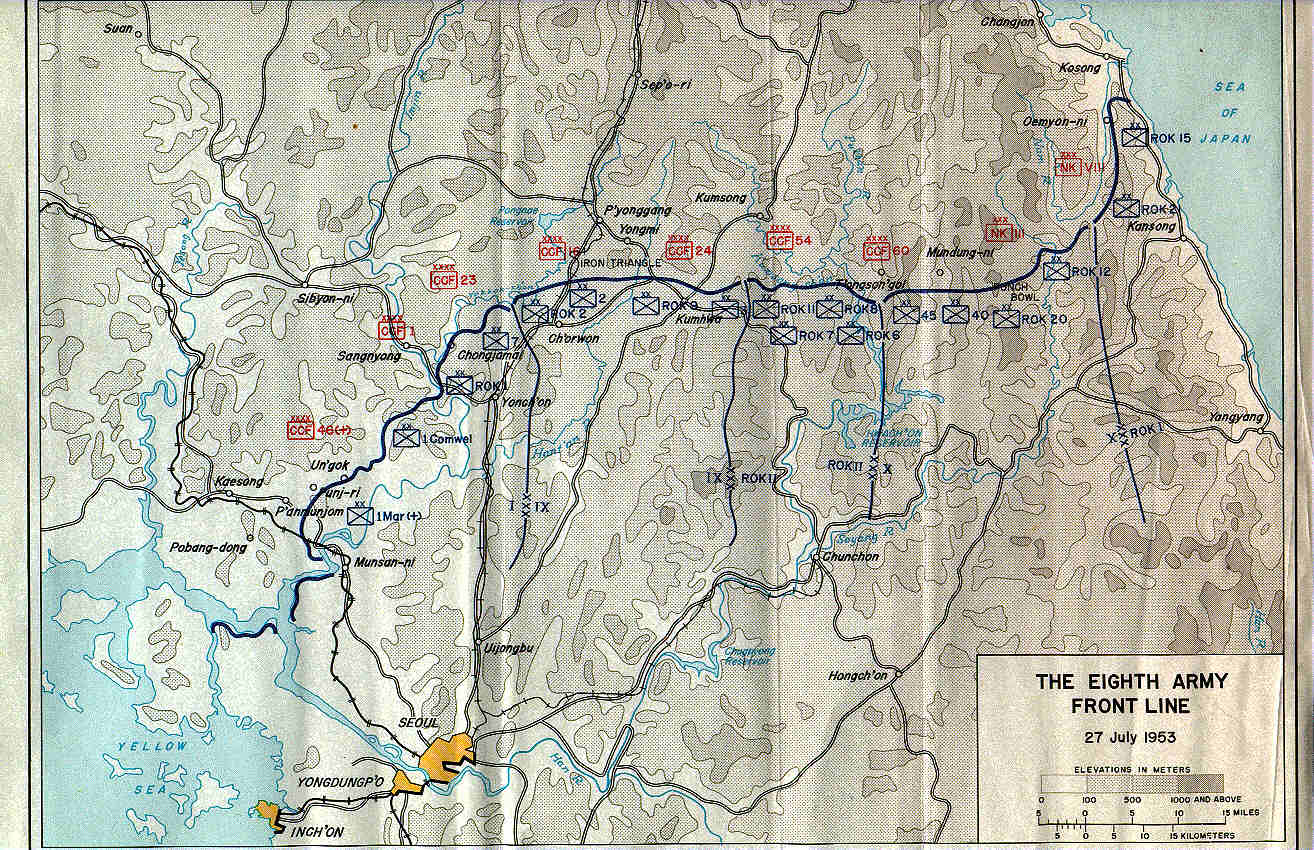

In May 1952,

the war was nearly two years old. The armistice talks at Panmunjom

were approaching the end of their first year without any hint of resolution.

On 12 May, General Mathew B. Ridgway passed the responsibilities of

the Commander in Chief, United Nations Command to General Mark Clark

and went to Europe to replace General Dwight D. Eisenhower as the

Commander of NATO. As the new commander in the Far East, Mark Clark

had his staff and subordinate commanders enumerate the options in

which he might be able to influence the Peace Talks through military

action.

The most

viable proposal came from General Otto P. Weyland; the new commander

of Far East Air Forces. Weyland proposed an all-out air attack on

the North Korean hydroelectric system. This system powered North Korean

industry that for the most part had gone underground to avoid UN air

attacks. A weakness of this proposal was in order to be decisive,

attacks had to be made against the largest power production plant

in the system--the Suiho hydroelectric plant on the Yalu River. This

strategic target had already received several reprieves since the

beginning of the war given its location on the border between China

and Korea. The possibility of UN aircraft mistakenly flying across

the border into Chinese airspace might provoke an escalation and expansion

of the war. In addition, the Suiho Dam provided approximately 10%

of the electrical power requirements of China's key industrial area

in Manchuria. Thus, striking Suiho would have a direct impact on China.

(5)

General Clark

directed that two sets of plans be prepared for attacks against the

hydroelectric system; one plan with Suiho as a target and one without.

These plans were then submitted the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington,

D.C. On 19 June 1952, the Joint Chiefs of Staff relayed to General

Clark that his plans to hit the North Korean hydroelectric plants--to

include the Suiho Dam--had been approved by President Truman.

Suiho Hydroelectric Plant, 23 June 1952

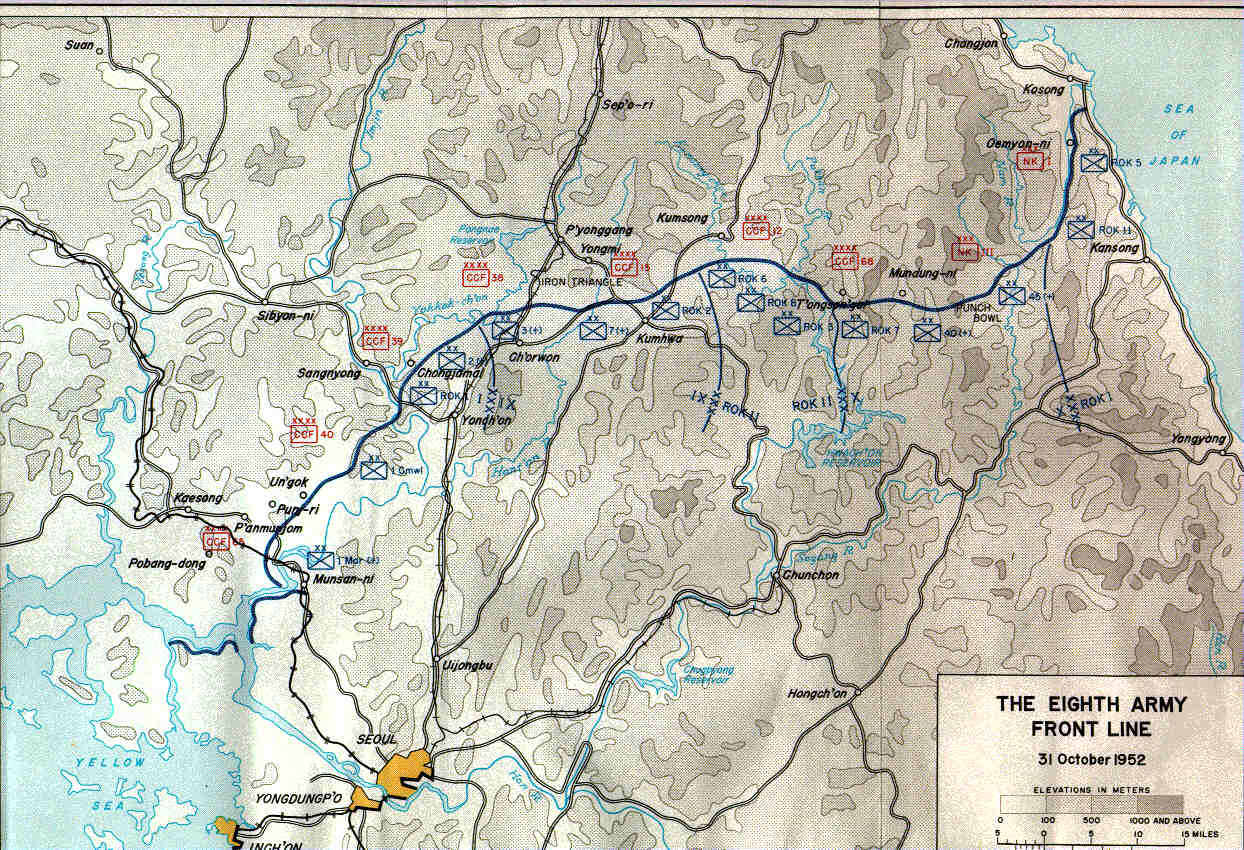

In the afternoon

of 23 June, the air offensive began with the combined attacks of US

Navy, Marine and Air Force aircraft on the Suiho Dam and the Chosen,

Fusen, and Kyosen hydroelectric complexes. Follow-up attacks occurred

on the 24th, 26th and 27th of June. When the smoke cleared, the lights

had been turned out all over North Korea and would remain that way

for at least two weeks.

When news

of the attacks on the Suiho Dam had been announced in the press, the

British Government reacted immediately with indignation and concern.

They had not been informed that the attacks were about to take place,

and the massive air strike on the Suiho Dam heightened its concerns

that the Korean War could expand into mainland China. British Parliament

demanded an explanation.

By coincidence,

U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson was in London when the storm

over the bombings had reached its peak. On the morning of 26 June,

Acheson addressed a group of members from both Houses of Parliament:

"Now

you ask me whether this was a proper action. To that I say: Yes, a

very proper action, an essential action. It was taken on military

grounds. It was to bomb five plants, four of which were far removed

from the frontier, one of which was on the frontier. We had not bombed

these plants before because they had been dismantled, and we wished

to preserve them in the event of unification of Korea. They had been

put into operation once more; they were supplying most of the energy

which was used not only by airfields which were operating against

us but by radar which was directing fighters against our planes.

My hearers

seemed to approve. They applauded heartily when in reply to a question

I said that the attack had been highly successful. Nevertheless, when

I met privately with Eden, he pleaded for “no more surprises.”

(6)

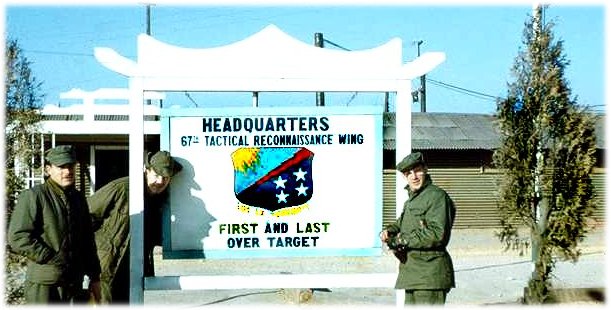

1800 Hours,

26 June 1952

67th Group Operations

Kimpo Airfield,

Republic of Korea

As Acheson

dealt with the uneasy Britons on the other side of the world, it was

evening in Korea. At Kimpo, operations and intelligence personnel

of the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group Ops began to compile the

list of recce missions that would be flown the next day -- June 27th.

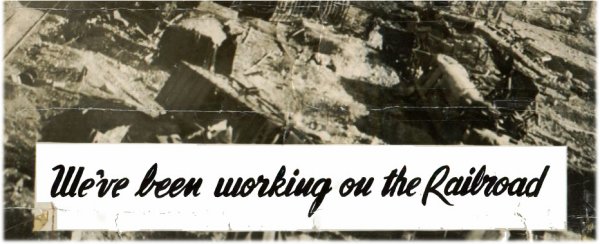

It is the

nature of things that all air operations start and end with Tac Recce.

As such, the 67th Group Ops played a vital role in the air war over

Korea. There were "routine missions" to assign to each of

the three squadrons in the group -- like the daily early morning run

over North Korea to gauge the weather, the weekly photography of the

enemy's front lines, and the periodic reconnaissance of bridges, rail

lines, and airfields to monitor the status of Communist repair efforts.

There were pre-strike missions to take target photography that would

be used by pilots and bombardiers in the medium, light, and fighter-bomber

squadrons to plan their attacks. And then there were the battle damage

assessment or "BDA" missions. After the air strikes went

in, Tac Recce pilots would return to photograph targets to see if

the bombers had accomplished their missions. With over 75 reconnaissance

aircraft in the group flying 100 to 150 sorties to per day, it took

quite an effort by the Groups Ops personnel to pull it all together.

By midnight, the target lists had been dispatched to the 12th, 15th

and 45th Squadrons.

*****

0400 Hours,

27 June 1952

15th TRS Operations,

Kimpo Airfield, ROK

Captain Cecil

Rigsby In June 1952, the squadron operations officer for the 15th

was Capt. Cecil R. Rigsby. Rigsby was an old hand at photo recon.

As a photo reconnaissance pilot during World War II, he had served

in the Pacific with the 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron in New Guinea.

Between November 1942 and April 1944, he flew 91 combat missions in

F-4 and F-5 reconnaissance aircraft. "About 10 of these missions

were fighter escort missions in the P-38H fighter", he remembered.

After the

war, Rigsby left the Army Air Corps to pursue civilian life as--a

photo recce pilot. Between 1946 and 1948, he was the chief pilot for

the Kargl Aerial Survey Company of Midland, Texas. He flew F-5s, AT-21s

and a BT-14 surplus WW2 aircraft--all had been converted to allow

for aerial photographic mapping. He photographed nearly all of West

Texas, New Mexico and much of Colorado for the USGS and Oil Companies.

He recalled later,

"When I left [the service], I was in the 39th Tactical Reconnaissance

Squadron--the fourth squadron of the 410th Fighter Wing--at March

Field, California. The Cold War heated up so the 67th Recce Group

was formed and the 39th Squadron was redesignated the 12th TRS.

Capt.

Clyde East and Lt. Cecil Grigsby, 1948I received a letter one day

in late 1947 asking me if I wanted to come back on active duty. If

I volunteered to come back on active duty I had to go back to 1st

Lt. and that is what happened. I went back into the 12th TRS, the

same one I was in before and found the squadron full of fighter pilots

who wanted to fly jets. Captain Clyde East was the Intelligence Officer

and I was assigned as his assistant. Between the two of us we flew

most of the aerial photography while the fighter pilots flew in formation

and engaged in aerial dogfights.

I arrived

in Korea in February 1952. I flew my first combat mission on 1 April

1952..."

Since the

first strike against the North Korean hydroelectric system on 23 June,

"The Cottonpickers" had been involved in BDA photography

for this air offensive. As squadron operations officer, Capt. Rigsby

planned the first BDA mission for the Suiho Dam strike. This recce

mission followed right on the heels of the Navy and Air Force fighter-bombers.

Escorted by 16 F-86 Sabre Jets, two pilots from the 15th flew their

RF-80s north to the Yalu and then paralleled the river to the northeast

towards the Suiho Reservoir. Deep inside Mig Alley, they began their

photo runs no less than 20 miles from the Chinese fighter base at

Antung. The Chinese and North Koreans had been surprised by the fighter-bombers,

but the gloves were off an hour later when the two "Cottonpickers"

made their runs in. Several antiaircraft batteries hammered away from

both sides of the Yalu as the RF-80s streaked in towards the huge

column of smoke and flame billowing from the Suiho power house. The

15th pilots got their photos, climbed to altitude, and returned to

base just as the sun began to set. The Russian and Chinese MiG-15s

at Antung never left the ground. The Tac Recce slogan, "First

and Last over the Target..." was no idle boast that day--from

either side of the Yalu. (6)

*****

"First

and last in squadron operations...", might be an appropriate

way of describing Capt. Rigsby's five and a half months in Korea.

The sun rose over Kimpo Airfield at 5:11 a.m. on 27 June, but he and

the squadron intelligence officer, 1st Lt. Keith E. Brown, were up

and at work long before that:

"We had a very big squadron with nearly twice the airplanes

and twice the pilots of a normal squadron. To fly as many as 50-combat

missions or more per day required nearly everyone who had a secondary

or primary job to work like hell. When you read about pilots going

into town, having fun off the base or hanging out each night at the

Cottonpickers, that life style didn't apply to those of us in Operations

and Intelligence and probably some other sections.

The Intelligence

officer and I would get up early in the morning and with help from

the noncoms, [we would] plot all the targets on a big map board in

grease pencil. At this point we would divide them up into missions.

We would all try to go to the Group Intelligence, Army Liaison, and

the Weather briefing each morning and then meet in Operations. The

pilots could look at the board and see where they stood in rotation

and would not leave until it was obvious they had a few hours before

being called upon.

We also

had missions coming to us from 5th Air Force during the day. I don't

believe I was in the Orderly Room or the Group Commander's Office

more than a couple of times during my entire tour. That is how busy

we were flying the missions and getting them off the ground. I'm glad

that I was only age 29 and able to work with not much sleep..."

In the 15th

Ops Hut, Capt. Rigsby and Lt. Brown reviewed the list of targets from

67th Group Ops. As they sketched out the scheme for accomplishing

the day's assigned recce tasks, Rigsby recognized one of the targets

on the list--Chosen Hydroelectric Plant #3. He was familiar with this

particular target; he had flown an RF-86 'dicing' mission against

it the previous day.

Capt.

Cecil Rigsby and Crew Chief - Kimpo 1952

The Chosen

Hydroelectric Plant #3 was located about half way between the North

Korean port city of Hungnam and the Chosen Reservoir. One of four

hydroelectric plants in the Chosen power system, Chosen #3 had been

hit by the 1st Marine Air Group on June 23rd. Air Force fighter-bombers

hit it again on the 26th. Rigsby flew his dicing mission after this

second strike. He was on his low-level photo run when he began to

receive fire from a heavy machine gun. I drew ground fire from a single

50-caliber machine gun firing tracer ammunition. The gun was along

the line of flight and tracers went above me and below the aircraft.

I held the heading and descending altitude long enough to ensure I

had good coverage". Rigsby got his pictures and returned to Kimpo

unscathed.

Today--according

to the target list he held in his hands?the 15th would be going back

to Chosen #3. Rigsby assigned aircraft and pilots to targets and discussed

the set up with Major Williams when he arrived at operations.

"I had the names of all pilots present for flight duty on a board

with little hooks so I could move them around. To insure that all

pilots fly their missions in rotation, I would give the next mission

up to the next pilot up if I thought he was experienced enough to

handle it. However, we may have had as many as 10 or more missions

to fly within a couple hours of each other. In this case I could be

selective. Also, we had to decide whether or not to assign an RF-80

or an RF-86. If the mission was more dangerous than others and the

RF-86 could do the job, we assigned the RF-86. I believe Jack Williams

was flying his missions in rotation, but as I recall he wanted this

mission."

Normally,

reconnaissance flights into the northeastern part of North Korea were

single aircraft recce missions. However, because of the antiaircraft

fire Rigsby received over Chosen #3 the day before, it was decided

that Williams should have an armed escort to suppress any enemy air

defenses in the target area. The next pilot "up" was Capt.

Clyde Voss.

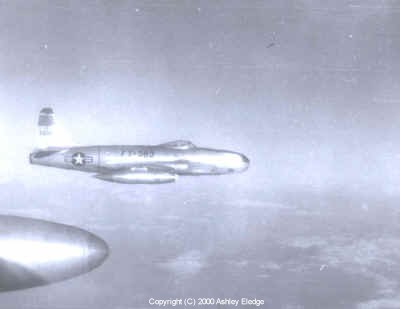

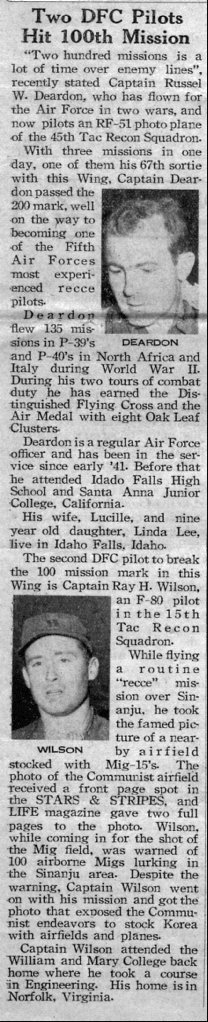

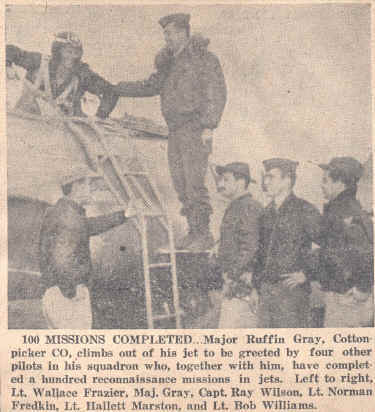

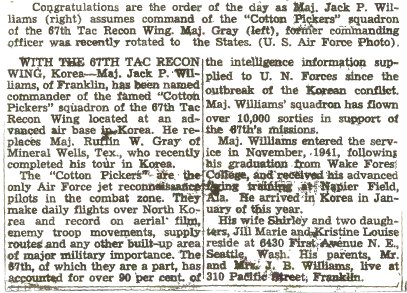

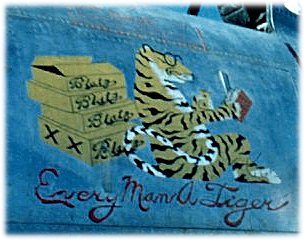

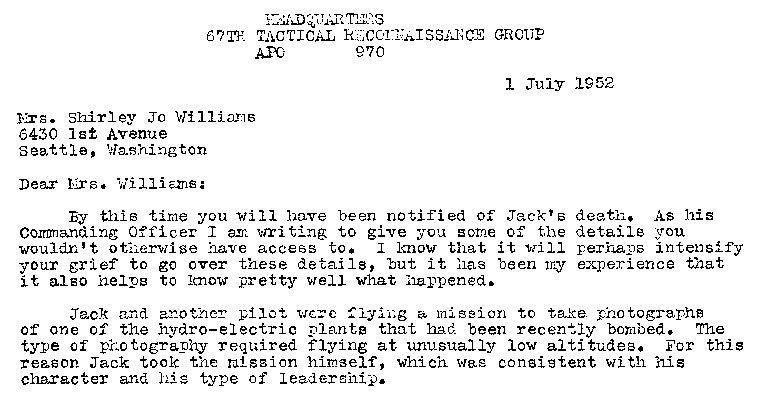

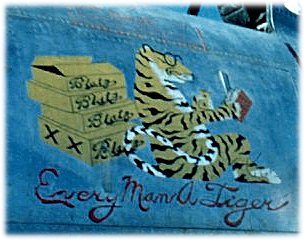

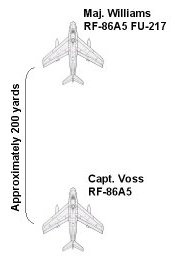

RF-86

FU-217 "Every Man a Tiger"

RF-86 Pilots of the 15th TRS pose in front of the aircraft in which

Major Williams was shot down. Major Jack Williams is standing at far

right. Captain Clyde Voss is standing fifth from the left (wearing

sunglasses). Capt. Cecil Rigsby is on the far left sitting on the

fuel tank. Photo taken in May-June 1952 timeframe.

Born in Texas,

Captain Clyde K. Voss attended Texas A&M before the start of WWII.

In December 1941, Voss was in his third year in college when the Japanese

attacked Pearl Harbor. He signed up for pilot training in the U.S.

Army Air Corps. Earning his pilot's wings, he was assigned to the

364th Fighter Group in England. He flew P-38 and P-51 fighters over

occupied Europe, and was credited with shooting down three German

aircraft. In September 1944, while flying his 68th combat mission,

he was shot down behind German lines. He managed to evade capture

with help of the Dutch underground.

When the Second

World War ended, Voss was assigned as a Fighter Gunnery Instructor

at Foster Field, Texas. In March 1946, he was transferred to the 1st

Fighter Group at March Field, Calif. Here he began flying the first

P-80 Jet fighters to enter service. In 1948, he was sent to the Pacific

where he was assigned to the 51st Fighter Group at Naha Air Base,

Okinawa. He continued to fly P-80s with the 51st Fighter Group until

1950. By June 1952, he was a veteran jet-fighter and photo reconnaissance

pilot and the commander of "B" Flight, 15th TRS. He was

also the squadron's Test Pilot and Instructor Pilot (IP) for the RF-86.

When Voss

arrived at operations, he was informed he would be flying that morning

with the squadron commander. Capt. Rigsby then briefed Williams and

Voss on their mission. It was a dicing mission consisting of two RF-86s.

Take off time would be 0915 hours. Williams would fly FU-217 and take

the photos; Voss would have hot guns and would suppress any antiaircraft

fire they received on the run in. Rigsby recalled,

"I briefed Jack Williams on the altitude to approach the

target, aiming of the aircraft, intervalometer setting and the ground

fire I had encountered the day before. This is the reason we sent

two airplanes. To get good photos at very low altitude with the 40"

focal length camera it was necessary to slow the RF-86 to avoid motion

in the lower 1/3 of the picture. The lens speed of this camera would

not compensate for high-speed low altitude passes. In all the missions

I flew with this camera I had to come in slow over the target. The

40" focal length camera did permit you to break off the target

before passing over it, or you were in your break when the airplane

went over the target. I also told him about the motion problem with

a high speed pass and that he should consider a slower approach, but

it was up to him.

Williams and

Voss discussed how they would approach the target and what they would

do if they received any ground fire. "It had been assumed that

if we were fired upon during the pass through the valley, I would

be the first to know. The idea was that if we drew fire and could

see the source, I would turn in on it and suppress it, " Voss

remembered. At around 0830, he and Williams had completed their flight

plan and went to the personal equipment hut to get suited up in their

flight gear. This completed, they walked to the flight line, pre-flighted

their aircraft and taxied for takeoff.

Capt. Jack

W. GriffisAt least two other 15th pilots were slated for missions

that morning; both were scheduled for take off less than an hour after

Williams and Voss. Capt. Rigsby was scheduled to take mosaic photography

of the enemy's frontline positions in an RF-80. Capt. John ("Jack")

W. Griffis, Jr. was scheduled to fly but his planned flight for that

day is lost to memory. We can be certain it looked nothing like the

mission he would actually fly. As the commander of "C" Flight,

15th Tac Recon Squadron, Jack Griffis' call sign was "Charlie

One".

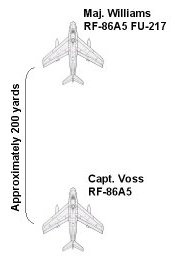

At 0915, Maj.

Williams and Capt. Voss were airborne and headed northeast. They climbed

to an altitude of 25,000 feet and proceeded across the peninsula towards

Hamhung; Voss was behind and to the left of Williams’ aircraft.

They soon crossed the bomb line and Williams reported this to the

Joint Operations Center (JOC).

After about

15 minutes, the pair of RF-86s was in the vicinity of Wonsan. Williams

began to descend into the target area. As planned, Voss fell to the

rear of Williams to get into his trailing, over watch position. Voss

remembered, “We descended toward the mountain pass from 25,000

feet. We reached the correct altitude to fly through. I was directly

behind and a little higher than Jack to be where I would better be

able to see if he came under fire. I was looking down at the target

area while maintaining position and watching him.”

At about five

miles out from the Chosen hydroelectric plant, they had descended

to about 3000 feet and were flying 100 knots slower than the planned

approach speed. “We were flying at about 275 knots. I urged

him to speed it up. He just once said, 'In a minute'. He sounded wide-awake”,

Voss recalled.

Thirty to

45 seconds out from the target they were still flying too high and

to slow; something was wrong. Voss called Williams but got no response.

Unknown to Voss, Williams had already spoken his last words.

“We had flown over the target hydroelectric facility without

getting down to the low altitude we planned. Williams’ plane

began to stream what appeared to be fuel from the wing root trailing

edges." Voss hadn't seen any muzzle flashes, tracers, or any

indication of weapons firing from the ground, nor had he witnessed

any rounds strike his aircraft. Nonetheless, William's was streaming

fuel. "I called Jack and told him he must have been hit and suggested

he turn left [south] and start for home. There was no answer from

him from that moment on, and no indications that any control inputs

[to his aircraft] were made.”

****

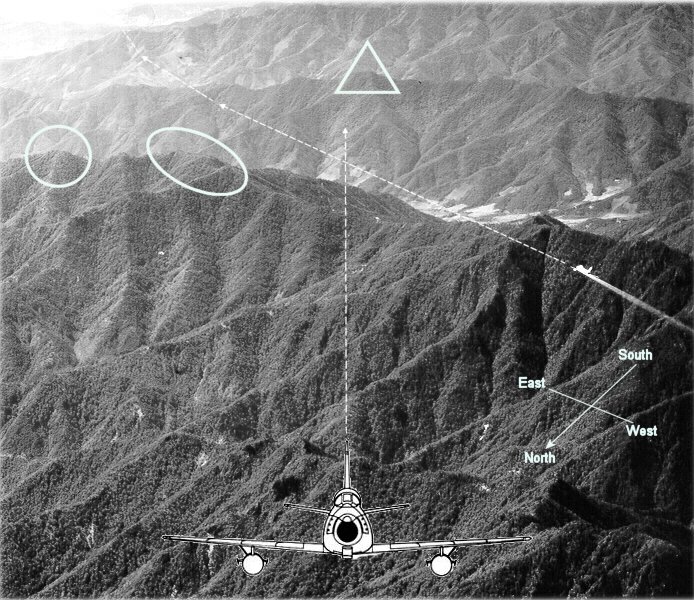

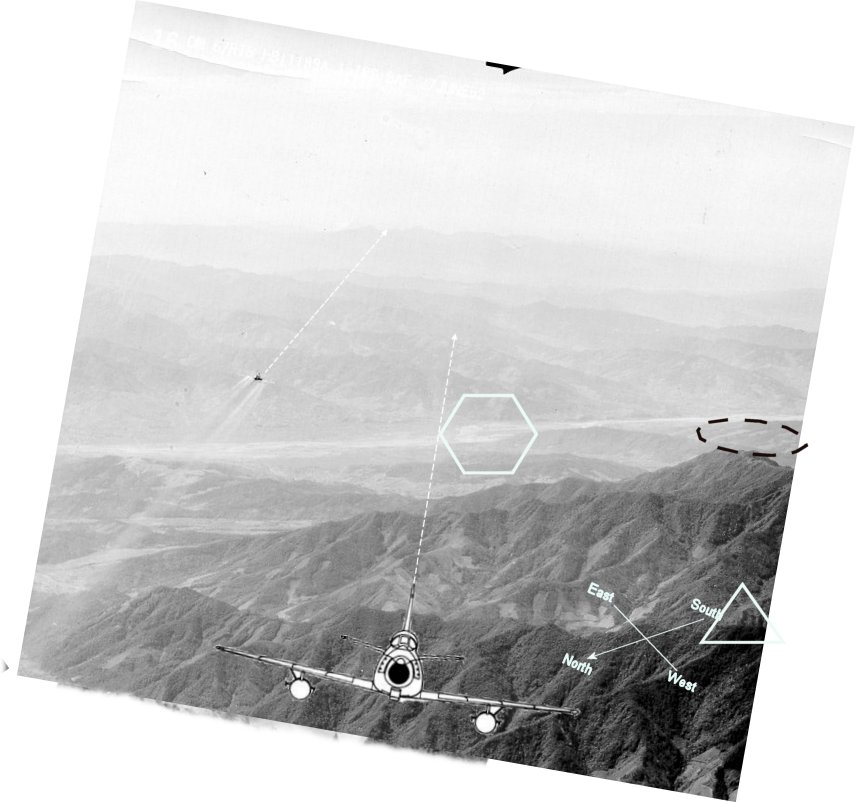

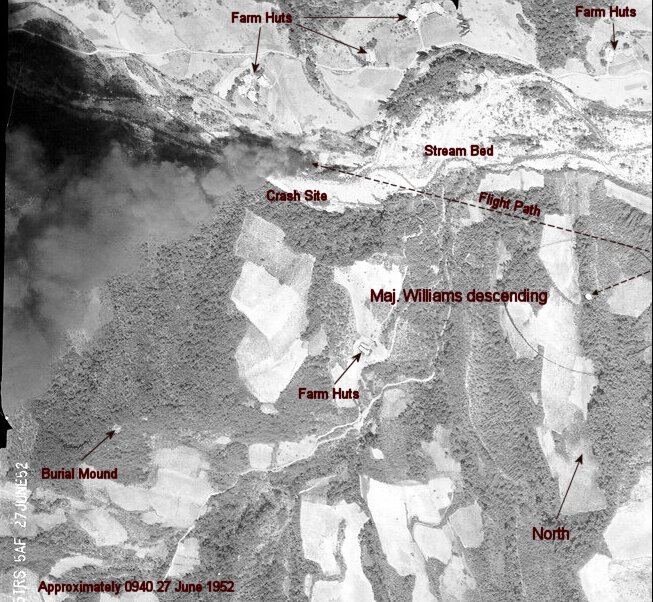

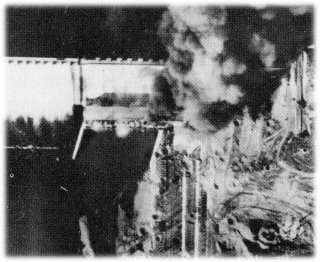

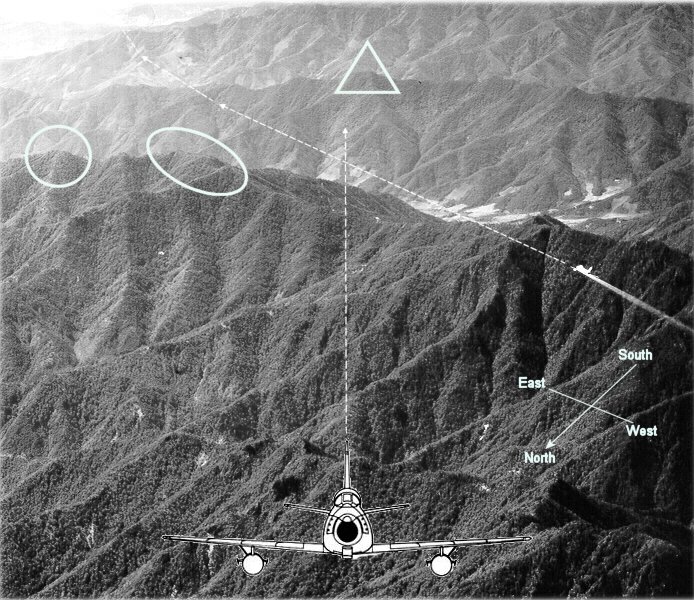

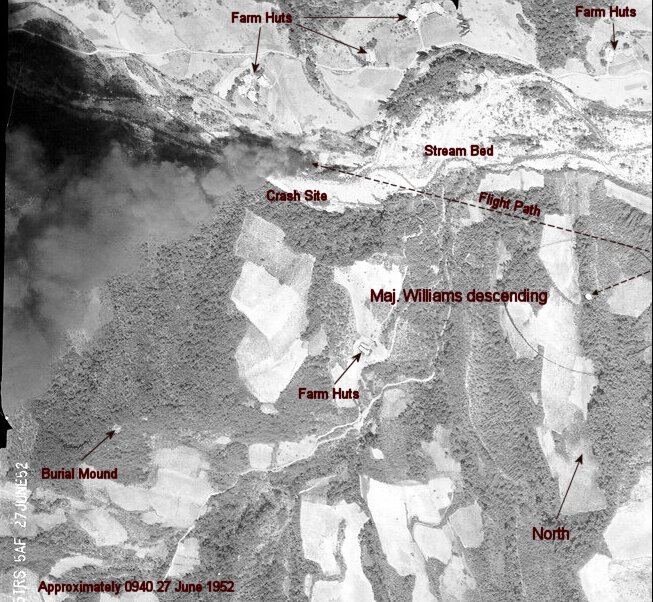

Frame

4: Fuel Streaming from Major Williams' RF-86A

t this point

occurred one of the most extraordinary incidents in the history of

the air war in Korea—Capt. Voss turned on his forward oblique

camera and started recording the events as they unfolded. Voss recalled,

“I began taking pictures with my foreword oblique camera when

I saw that he was losing fuel. I operated the camera manually when

I actually had something to photograph. His airplane began a gradual

climb and gentle turn away from home. His speed changed very little

from that time on except for the normal slowing [that would occur]

as the airplane began its very gentle climb--and very slight turn

to the right [north]. We passed over the mountains that formed the

northern part of the valley the river flowed through, and his airplane

continued to turn until it was heading east, climbing gradually.”

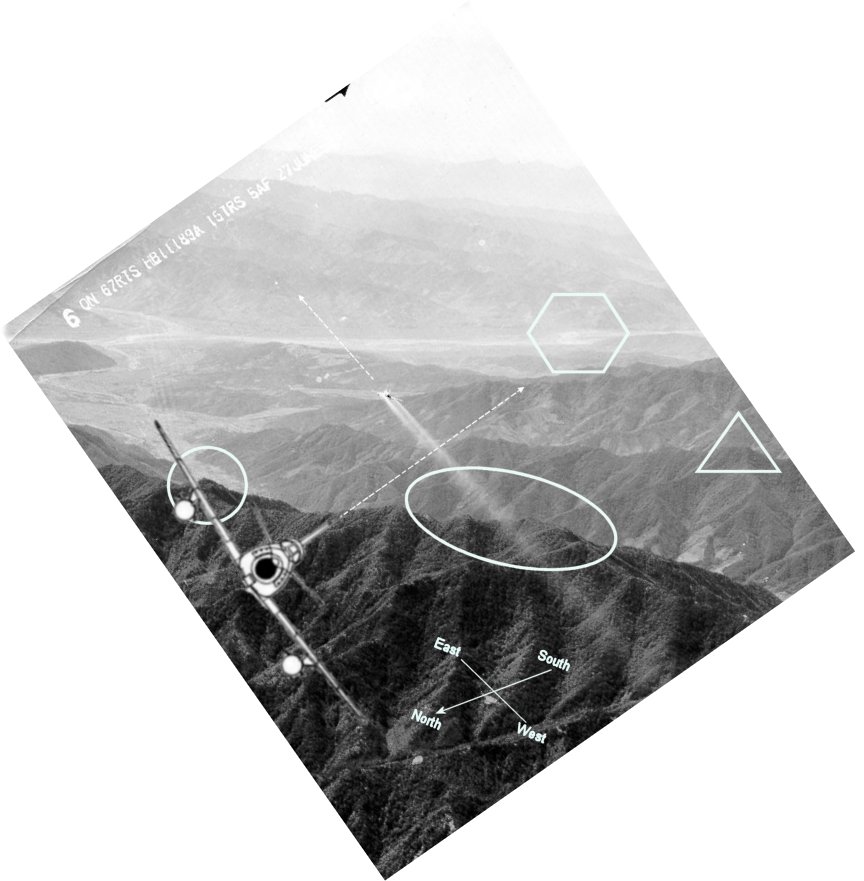

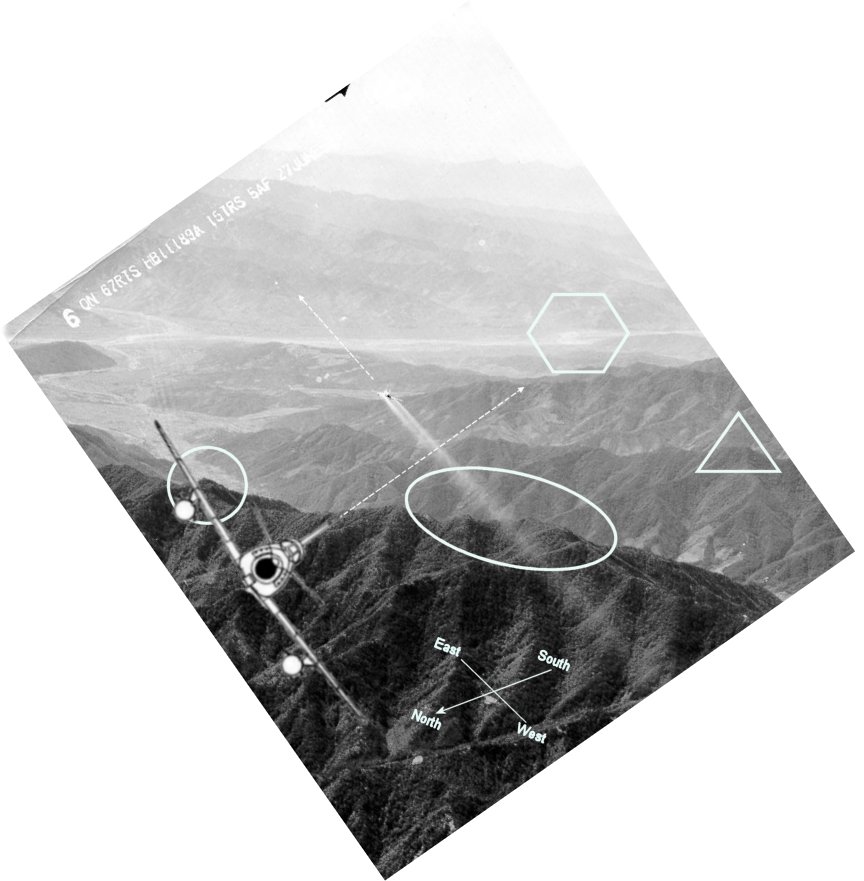

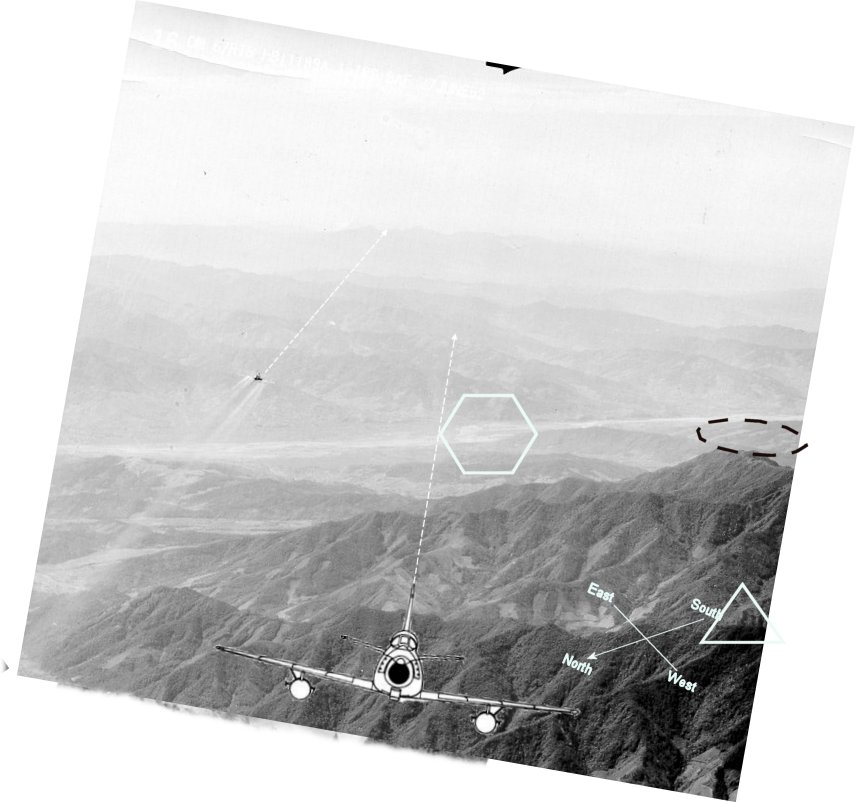

Frame

6: Capt. Voss maneuvers to Williams right side

Frame

16: Capt. Voss closes on Williams' right side

Voss maneuvered

his aircraft from a position at Williams’ left rear to close

to his right wing. He hoped to get in close enough to see what was

going on in Williams' cockpit.

I couldn't see in the cockpit it was so full of smoke. Fire was

coming out of the fuselage behind the cockpit. I kept calling him

and telling him to bail out. From the time I first saw the fuel streaming

out around his wing roots, I couldn't raise him on the radio. At this

point the plane rolled to the right and into me rather abruptly. I

pushed over hard to avoid a collision as he passed over me and continued

rolling. [This] caused him to get behind me. The last I saw him, his

canopy was still on. I maneuvered hard to regain sight of him..."

and when I next saw him, his chute was deployed. I finally turned

enough to get the scene in my windscreen and took a few pictures.”

As Voss maneuvered

his RF-86 in a high-rate turn to the right, he caught sight of Williams'

plane below him as it impacted into the ground in a huge fireball.

Then, an encouraging sight--a deployed parachute descending to the

ground a hundred yards or so from the burning wreckage.

"After

the airplane crashed and the chute was on the ground, I made calls

for rescue and dived down around the scene. It was obvious that Jack

was not moving about though I could not see enough to tell what his

condition was. I was operating at very low-power to conserve fuel

so I was neither very low nor very fast. It is safe to say that I

was under 1,000 feet above ground level.

On one

of my runs past the crash site, I saw some local farmers who were

moving toward the chute. I strafed the ground a couple of hundred

yards in front of them. I had mixed feelings about whether he would

be better off if the local farmers could get to him or if we kept

them away. On the strafing run, I was not aiming at anything. I was

just spraying some rounds between the Koreans and Jack’s burning

aircraft. I didn't want to hit any of them; I just wanted to say,

“Stay back....”

After each

low-level run past the crash site, Voss climbed back to altitude to

continue his calls for assistance.

"Mainly

I needed to be above the mountains to make radio contact with someone

to help. I was short on fuel and trying to stay low enough to keep

Jack in sight on the ground. I knew I had only a limited time to CAP

[Combat Air Patrol]. I made a blind call on the Guard channel for

anyone at high-altitude to relay my call for anyone with sufficient

endurance to [replace me and] serve as a CAP.”

Approximately

0945 27 June 1952

15th TRS Operations Hut

Kimpo Airfield (K-14)

Griffis:

“I

was in operations when the word came in. It was a call from Clyde

and the location [of the crash site]. For some reason I had my gear

and was ready to fly. I must have had maps with me because someone

said where the mission had been. I knew exactly where to go. I vaguely

recall having been briefed on the hydroelectric plants and that I

had the locations on my maps. I went directly to the 45th Tac Recon

Squadron [flight line]. We went to the nearest F-80 that had people

near it. I seem to recall getting out of a vehicle so someone must

have driven me there. I told them that our squadron commander was

down and needed a CAP. I asked them if they had an F-80 ready to go.

They pointed me to the nearest one and someone said it was ready to

go with hot guns. I got in and took off. I didn't ask anyone's permission.

I think I was on the runway in 10 minutes or less after the word had

come in. [Once airborne] I went full bore to the scene...”

****

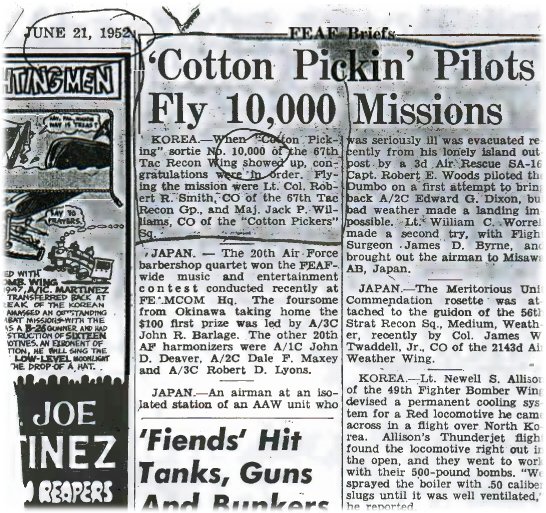

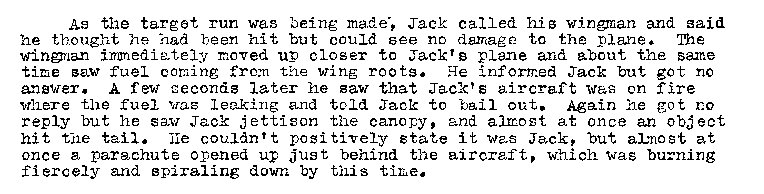

U.S.S.

Iowa off Wonsan, April 1952

The Battleship U.S.S. Iowa off Wonsan, North Korea - April 1952

It is probable that the HOS-1 helicopter at the stern is the aircraft

that picked up Major Williams.

Approximately

0945 27 June 1952

U.S.S. Iowa

Task Force 95 (Blockade and Escort Force - Rear Admiral J. E. Gingrich)

Sea of Japan

[U.S.S. Iowa

receives/monitors request for search and rescue and dispatches helicopter...Strong

possibility the aircrew of this helicopter was Navy LT Robert L. Dolton

and AM1 Willis A. Meyers. Dolton and Meyers had rescued LT(JG) Harold

A. Riedl on 16 July 1952 after his F4U was shot down 30 miles northwest

of Hungnam. This rescue occurred eleven days prior to Major Williams

being shot down.]

****

Voss:

“After

several attempts I got a reply from some Marines who said they were

in the area in Corsairs and could be there in 10 or 15 minutes. We

met at an agreed altitude and I led them to the site. With all the

smoke it was easy to find. Once I pulled up above the mountain to

start home, I heard the Marines talking as they approached the site

and it was a thrill to hear how gung ho they were to do the job. My

thought was that with those guys circling Jack, no one other than

the rescue people would be allowed to get within a mile of him.

The helicopter

was in contact with the fellow at altitude to relay my distress calls

and while they were on their way, they asked if the downed airman

was alive. That was relayed to me by the high CAP pilot. Of course

I answered ‘Yes’, because I didn't know what his condition

was. I only knew that he was on the ground and not moving. Chances

are good, I thought, that he was unconscious or disabled, but alive.

With that report the helicopter crew came on in.”

Griffis:

“When

I arrived at the site, there was a single Corsair circling in the

valley [and] I checked in with him. Something was said on the radio

about someone chasing a couple farmers away from the chute. I had

to make my passes down the valley as I could not turn between the

hills. Williams was lying on the corner of the chute in an open area.

I made a couple of passes down the valley before I noticed the chopper.”

U.S. Navy

HO3S1 HelicopterUsing the smoke from the burning remains of FU-217,

the helicopter crew was talked in to Williams’ location. “The

rescue chopper arrived and hovered off to the side and above the chute”,

Griffis recalled. They hovered over his location to get a good look

at him; the downdraft of the rotor blades buffeting the grass and

Williams’ parachute. After a moment, the helicopter pilot reported,

“He looks dead."

[last Voss

photo]

Griffis, orbiting

overhead, heard the call. He toggled his mike and said, “This

is Charlie One. Pick him up...” Griffis received no response.

Frustrated, he called again, “This is Charlie one. Pick him

up, over…” For some reason, Griffis could hear the helicopter

crew but they could not hear him over the radio. Sensing a commo problem

between the two, the CAP pilot relayed Griffis’ instruction

to the rescue helicopter. The helicopter pilot’s answer to the

CAP was garbled but what Griffis did hear was, “…he looks

very dead…don't pick up dead...” Angered by this response,

Griffis burst over the radio, “PICK HIM UP!” The CAP pilot

immediately relayed to the helicopter, “Charlie One says, PICK

HIM UP!"

At last, the

chopper pilot acknowledged he would do just that. To assure the helicopter

crew of their safety, Griffis suggested to the CAP that they fly strafing

runs on either side of the helicopter when it went into land. This

they did as the helicopter went in to pick up Williams.

Capt. Rigsby

flying about [x] miles to the south recalled, "I was airborne

on a mission in east Korea. I heard nearly all the communications

while performing my mission. It took the helicopter a long time to

get to the site where Jack had landed. I heard the chopper commander

say, "OK boys, we are going in now, so stay alert..."

The helicopter

came in fast and settled on the ground in the open area next to Williams.

A Navy air crewman got out of the helicopter and ran to Williams’

body. By some means, the crewman freed Williams from his parachute

and dragged him onto the aircraft. The helicopter lifted off from

the scene, and after several minutes, Rigsby heard the pilot say,

"We are clear of the area now..."

As the helicopter

exited the area, Rigsby heard a voice on the radio ask, "How

is the pilot?"

"I will

never forget the words of the helicopter commander", Rigsby remembered.

"The pilot is dead, very dead'."

As Capt. Voss

headed south, his fuel gauge indicated that he had remained in the

area above Williams as long as his fuel supply would permit:

“I

was past our briefed ‘Bingo’. I was thinking what the

minimum fuel requirement was to get to Kimpo. I planned to drop my

external tanks when they were empty but after starting to climb out

toward home I discovered that they refused to jettison. I spent too

much time and energy, I'm sure, trying to get them to fall off, but

finally one came off when I pulled several quick Gs. A little later,

the other came off.

I flew

directly toward what I thought to be the nearest friendly territory

and when I saw I could make that, I turned directly toward Kimpo.

On the way home, I stayed in contact with the first CAP who relieved

me and I asked about Jack's condition he told me that the helicopter

crew reported that he was ‘very dead’. I asked no further

questions.

After

landing, I didn't bother to see how many actual gallons I had left,

but the gauge was reading empty when I landed. I had enough to taxi

in...”

Voss:

“It

is my opinion that the ground fire hit his cockpit as well as other

places and that he was disabled at that time. At no time after that

did the aircraft show any signs of pilot control inputs. His cockpit

was so full of smoke that I believe he would have ejected well before

the seat ejection was activated—[which] I believe [was caused]

by the fire [in the aircraft].”

****

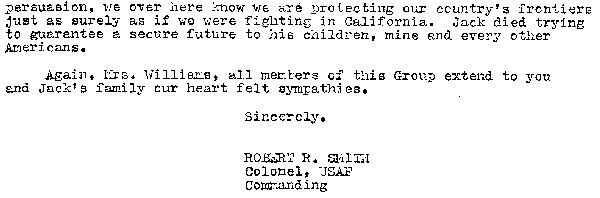

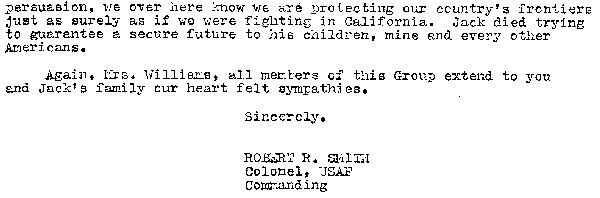

Shirley

and Jack Williams - Wedding Day

9/5/44 - Ft. Lawton, WA

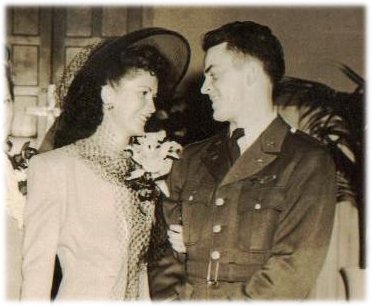

"Col.

Gabreski WWII Ace came to pay respects. He knew Dad in Korea."

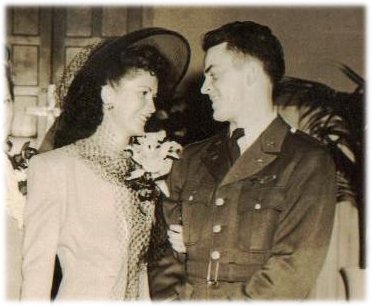

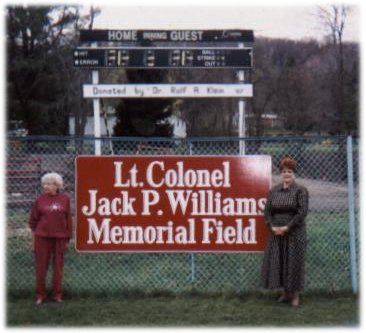

Kris and

Shirley Williams at Jack Williams' final resting place

Kris Williams--like

her father--learned to fly...

"I

loved the 'JP' in the aircraft number of my plane. My father...was

sometimes called 'JP'. I always felt Dad was with me when I was flying."

****

"Even

though Dad's time on earth was far too short, his footprint was very

large. He touched the lives of many individuals, who have never forgotten

his goodness and the extraordinary kind of man his was. Dad is my

standard in all that I do in life." -- Kris Williams, 2002

|